$$ \newcommand{\dede}[2]{\frac{\partial #1}{\partial #2} } \newcommand{\dd}[2]{\frac{\mathrm{d} #1}{\mathrm{d} #2}} \newcommand{\divby}[1]{\frac{1}{#1} } \newcommand{\typing}[3][\Gamma]{#1 \vdash #2 : #3} \newcommand{\xyz}[0]{(x,y,z)} \newcommand{\xyzt}[0]{(x,y,z,t)} \newcommand{\hams}[0]{-\frac{\hbar^2}{2m}(\dede{^2}{x^2} + \dede{^2}{y^2} + \dede{^2}{z^2}) + V\xyz} \newcommand{\hamt}[0]{-\frac{\hbar^2}{2m}(\dede{^2}{x^2} + \dede{^2}{y^2} + \dede{^2}{z^2}) + V\xyzt} \newcommand{\ham}[0]{-\frac{\hbar^2}{2m}(\dede{^2}{x^2}) + V(x)} \newcommand{\abs}[1]{\left|\left| #1 \right|\right|} \newcommand{\unit}[1]{\, \mathrm{#1}} \require{mathtools} \newcommand{\abk}[1]{\langle #1 \rangle} $$

Introduction and Basics

Topics Covered

- Complex stability (18 electron rule, electron counting)

- Ligand substitution generalities: BDE, kinetics and mechanism

- Stereochemical and electronic effects in ligand substitution

Metal Stability

A very simple rule to assess the stability of a transition metal complex is the 18 electron rule: If the metal has 18 valence electrons, that leads to more stability. It can be rationalized by the full shells of transition metals: $3d^{10},$ $4s^2,$ $4p^6.$ However, this does not mean that in all transition metal complexes, the rule is followed. There are many other factors that influence the stability, such as the ligands, the geometry, and the oxidation state of the metal.

Electron Counting

To determine the electron count of the metal, we show two formalisms:

Neutral Ligand Formalism

In the neutral ligand formalism, the complex is first split in fragments with a neutral charge on the atom that exhibits the dative bond to the metal:

$$\ce{L_nMX_x -> M + nL: + xX*}$$

The ligands are classified in L- and X-type ligands. The L-type ligands are the ones that donate two electrons to the metal, while the X-type ligands donate only one electron. The valence electron count is then given by the sum of the electrons on the metal (group number - charge) and the electrons donated by the ligands. The oxidation state is given by the number of x-type ligands and the charge of the metal and the number of d-electrons corresponds to the difference between the group number and the oxidation state. Consider the examples below:

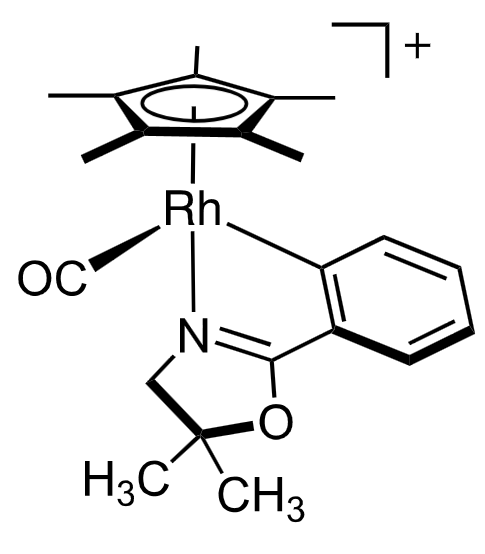

The carbon monoxide and the nitrogen are L-type ligands, while the aryl and the $\ce{Cp^\ast}$ are X-type ligands. The $\ce{Cp^\ast}$ however, is a special case: It can be thought of as an X-type ligand (the negative charge) with two additional L-type ligands (the double bonds) and thus donates 5 electrons. As Rh is in group 9 and we have a charge of +1, the valence electron count is $2 \cdot 2 \, (\ce{CO, N}) + 1 \, (\ce{aryl}) + 5 \, (\ce{Cp^\ast}) + 9 \, (\ce{Rh}) - 1 \, (\ce{charge}).$ The central atom is in oxidation state $\ce{Rh(III)}$ and it has $9 - 3 = 6$ d-electrons.

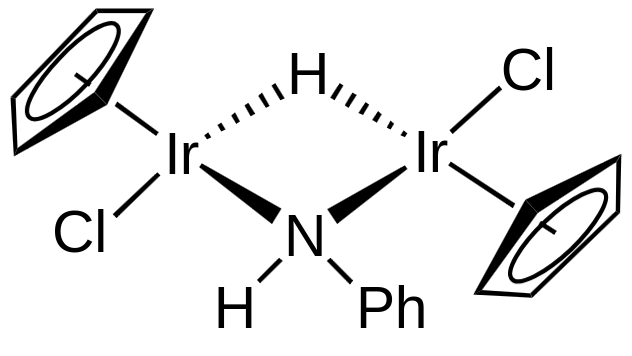

In this case, the hydride and the N-ligand are L-type with respect to one Ir atom, while being X-type to the other. This gives an electron count of $2 \, (\ce{L-type N/H}) + 2 \cdot 1 \, (\ce{X-type N/H}, \ce{Cl}) + 5 \, (\ce{Cp}) + 9 \, (\ce{Ir}) = 18$ for both $\ce{Ir}$ atoms. The oxidation state is $\ce{Ir(III)}$ and the d-electron count is $9 - 3 = 6.$

Oxidation State Formalism

For some people it might be more intuitive if ligand/complex bonds are split in heterolytic manner, affording charged fragments:

$$\ce{L_nMX_x -> M^{x+} + nL + xX-}$$

This also allows us to count the electrons easily: The oxidation state of the metal is given by the charge of the metal and the number of d-electrons is again the difference between the group number and the oxidation state. The valence electron count is then given by the sum of the electrons on the metal and the electrons donated by the ligands, which are usually two. Also here we consider two examples:

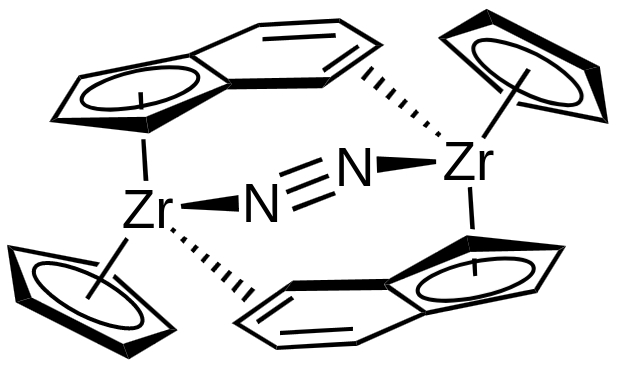

On each $\ce{Zr}$ there are two charged ligands, which gives the oxidation state $\ce{Zr(II)},$ leading to $d^2,$ as $\ce{Zr}$ is a group 4 element. The conjugated 5-membered rings donate 6 electrons each, while the other ligands donate two electrons each, which gives a valence electron count of $18.$

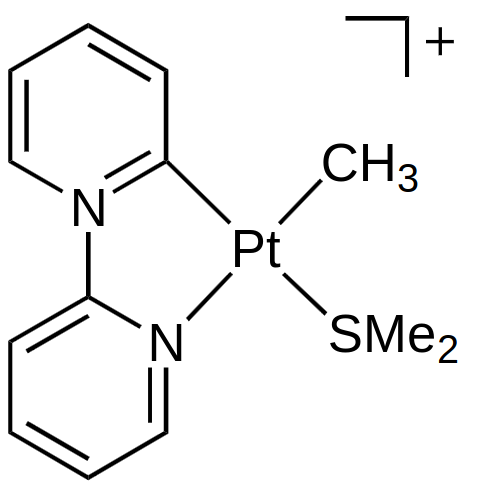

Here we have one charged ligand (the ligand on the left is not charged, there is a positive charge on the N) and the complex has a positive charge, which gives the oxidation state $\ce{Pt(II)}$ and $d^8.$ The ligands donate 2 electrons for each bond, which gives a valence electron count of $16.$

Sometimes determining the oxidation state can be tricky, because the ligands can take different form, such as with the following example:

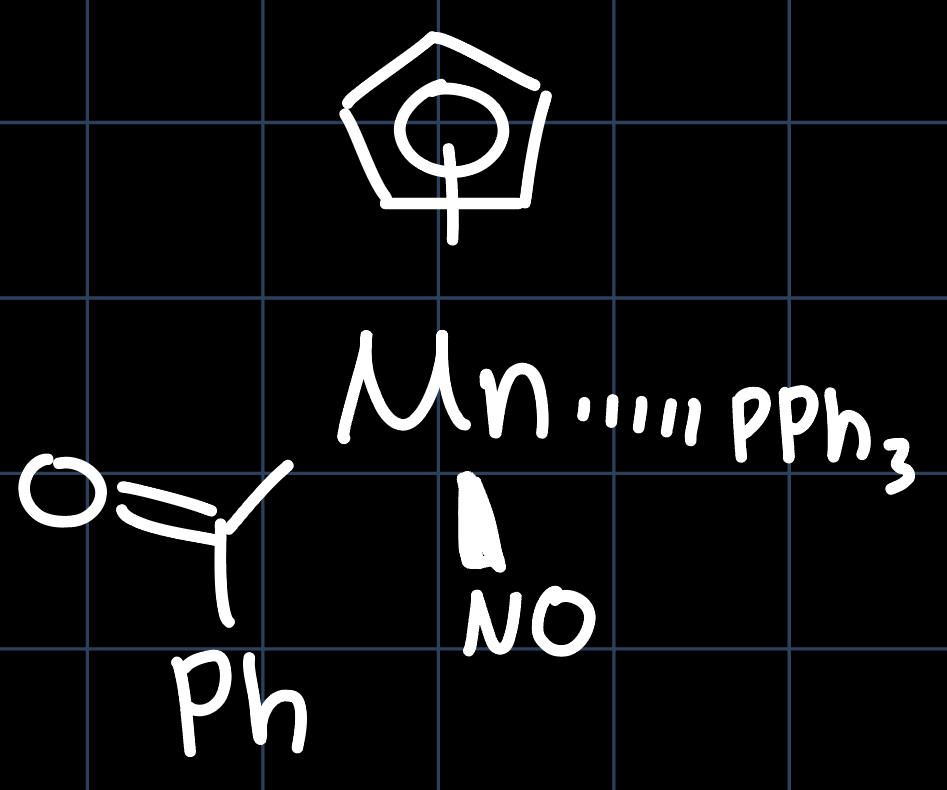

The $\ce{NO}$ ligand could potentially appear in different geometries: bent as X-type ($\ce{M-N=O}$) or linear as XL type ($\ce{M=N=O}$). The valence electron count $16$ in the bent case and $18$ in the linear case.

Application 18 Electron Rule

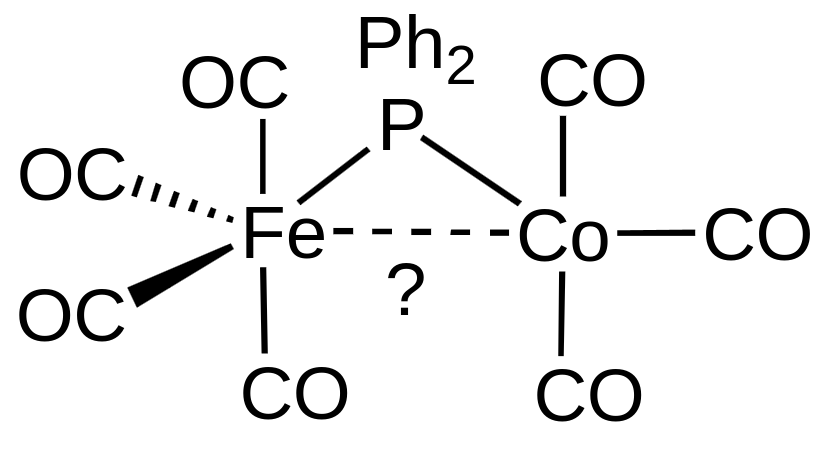

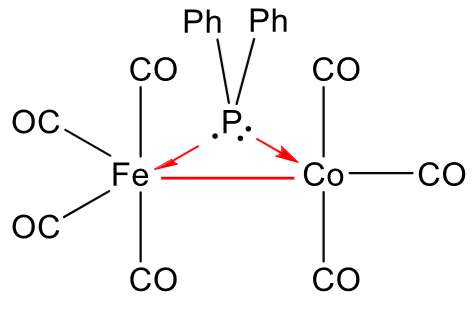

We demonstrate the application of the 18 electron rule on the following example: Considering the complex

we want to find out if it exhibits a metal-metal bond or not. Counting the electrons on both metals, considering the diphenylphosphine an X-type ligand for $\ce{Fe}$ and an L-type ligand for $\ce{Co},$ we get a valence electron count of 17 for both metals. Adding a metal-metal bond gives one more electron to each metal (as the bond is formed by two electrons, one from each metal), which gives a valence electron count of 18 for both metals. This means that the complex is stable and the metal-metal bond is present.

Ligand Substitution

$$ L_nM-X + Y \rightarrow L_nM-Y + X $$

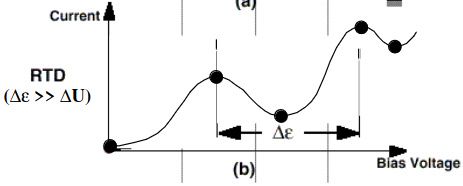

Understanding ligand substitution (LS) is essential to learning about the reactivity of transition metal complexes. LS are equilibrium reactions and always occur if we have a complex in solution. Designing ligands with specific properties, the equilibrium can be shifted and kinetic effects can be exploited to achieve selective reactions. Some important trends to remember are associated with the bond dissociation energy (BDE):

- The BDE for $\ce{M-L}$ increases with the period of the metal (for the same group and ligand)

- For the same metal, the DBE decreases in the following order of ligands:

$$ \ce{Cp} > \ce{C6H6} > \ce{CO} \approx \ce{PPh3} > \ce{NH3} > \ce{py} > \ce{H2O} > \ce{F-} > \ce{Cl-} > \ce{Br-} $$

Such trends can be physically reasoned: $\ce{Cp}, \ce{C6H6}$ offer "many bonds", larger halogens are less basic and thus they form weaker bonds to electropositive elements such as transition metals, etc.

For synthesis, the trans-effect can be exploited in order to achieve selective LS. The reaction rate for the substitution of a ligand $\ce{X}$ by a ligand $\ce{Y}$ is influenced by the ligand $\ce{L}$ that occupies a position trans to $\ce{X}.$ Strong $\pi$-acceptor ligands lower the energy of the transition state and strong $\sigma$-donor ligands destabilize the energy of the ground state. Both lead to a lower activation energy and thus a faster reaction rate. An empirical order is given by the spectrochemical series:

$$ \ce{CO}, \ce{CN-}, \ce{C2H2} > \ce{PR3}, \ce{H-} > \ce{CH3-}, \ce{Ph-} > \ce{Br-} > \ce{Cl-} > \ce{NH3}, \ce{py} $$

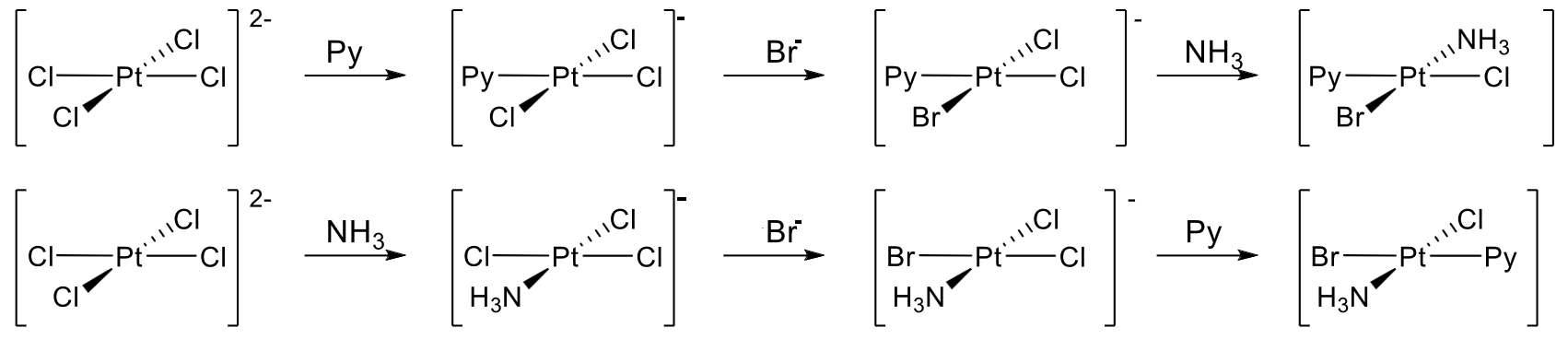

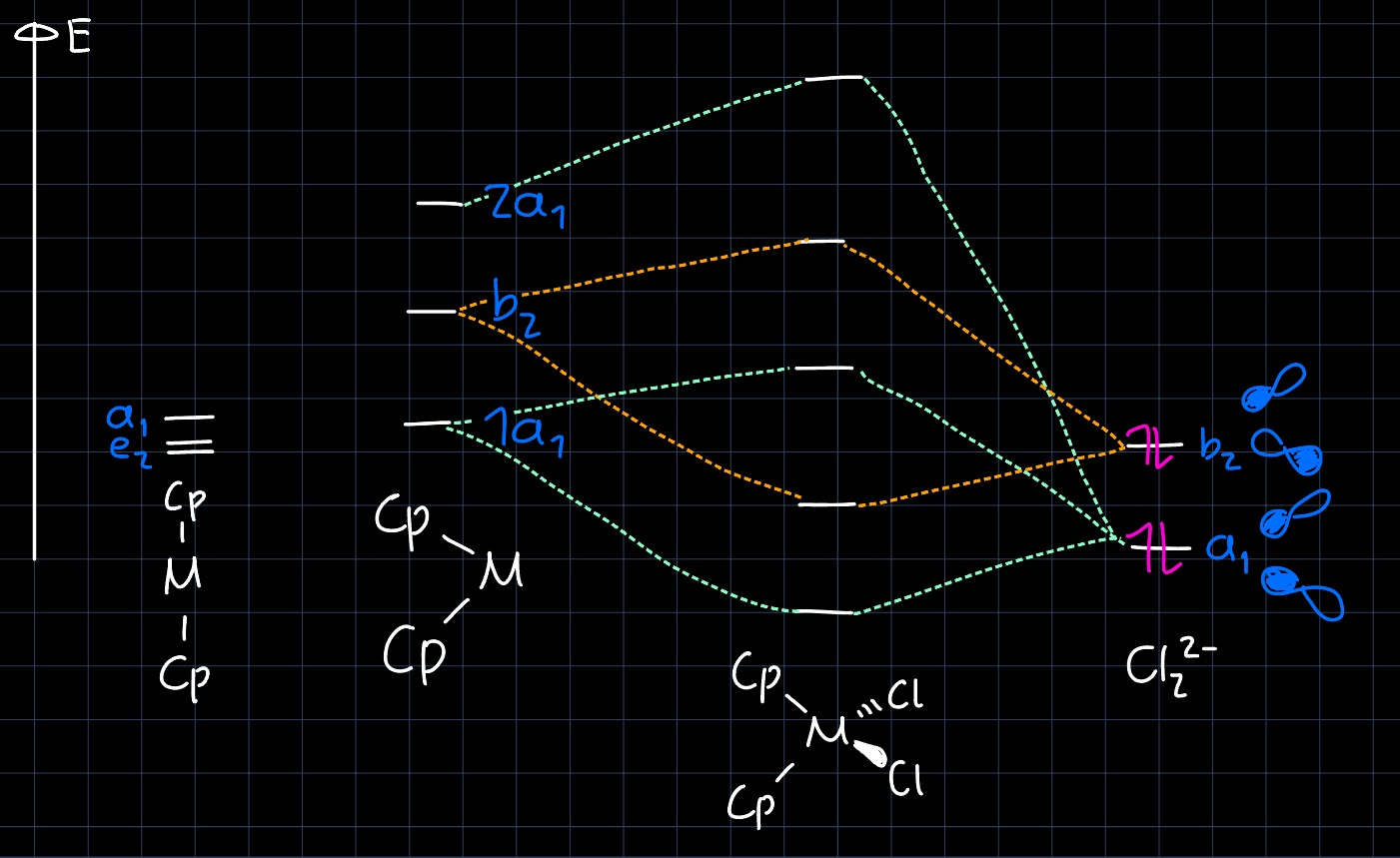

Using this series, we can setup a synthesis strategy, demonstrated by the example of making $\ce{[Pt(Cl)(Br)(NH3)(py)]}$ with the halogens in cis-conformation, starting from $\ce{[PtCl4^{2-}]}:$

- Start with $\ce{[PtCl4^{2-}]}$ and add $\ce{py}$ to replace one $\ce{Cl-}$ ligand.

- Add $\ce{Br-}$ and replace a $\ce{Cl-}$ ligand cis to the $\ce{py}$ ligand, as the trans effect for $\ce{py}$ is weaker than for $\ce{Cl-}.$

- Add $\ce{NH3}$ and replace the $\ce{Cl-}$ ligand trans to the $\ce{Br-}$ ligand, as the trans effect for $\ce{Br-}$ is stronger than for $\ce{py}$ and that for $\ce{Cl-}.$

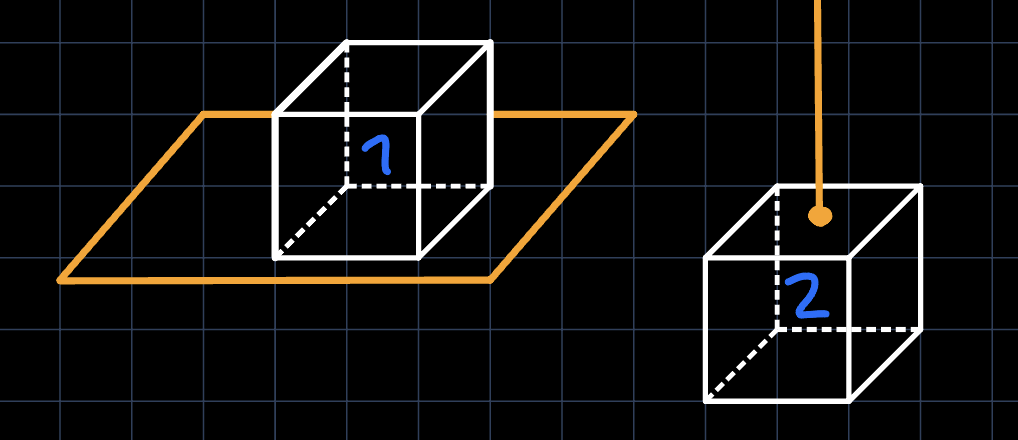

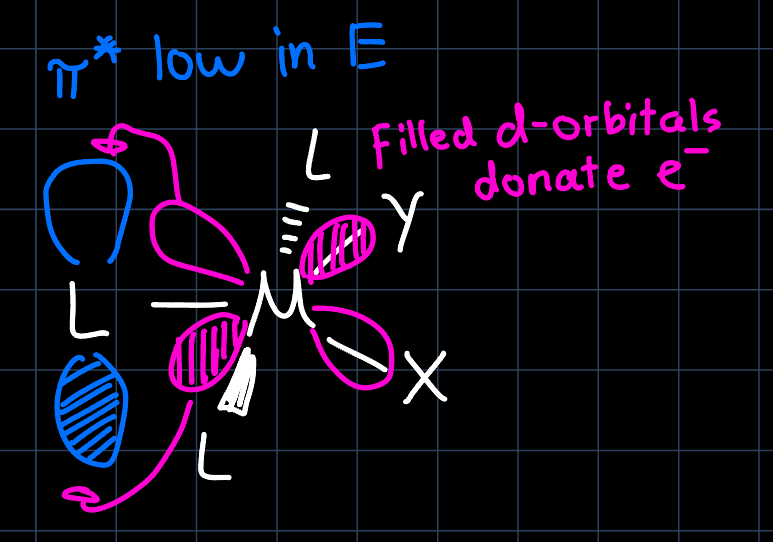

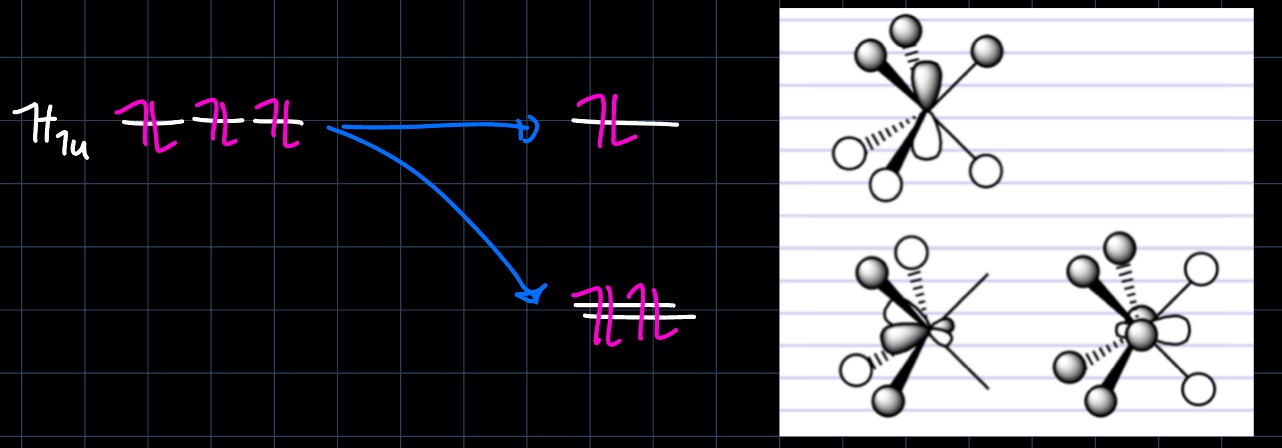

To understand why the trans-effect occurs, we discuss the two cases mentioned separately: The $\sigma$-donor ligands donate low energy electrons into the metals p-orbitals, which are however filled already filled. The filled-filled interaction leads to a destabilization of the ground state, however the transition state for the LS with the ligand trans is less destabilized (for the geometry, see image below). The $\pi$-acceptor ligands accept d-electrons from the metal, leading to a stabilization of the transition state:

Metal Hydrides, Pd cat. Cross Coupling and KIE

Topics Covered

- Metal Hydrides: $\ce{L_nM-H}$

- Pd-catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions

- (Inverse) Kinetic Isotope Effects

Metal Hydrides

Metal hydrides are a class of compounds that contain a metal atom bonded to a hydrogen atom. They are called metal hydrides because the oxidation state of the hydrogen is $-1$, but they are not necessarily hydritic. The cleavage of the $\ce{M-H}$ bond can occur in three ways:

$$ \begin{aligned} \ce{M-H &-> M- + H+} &\quad (\mathrm{pK_a}) \\ \ce{M-H &-> M^. + H^.} &\quad (\mathrm{BDFE}) \\ \ce{M-H &-> M+ + H-} &\quad (\mathrm{\Delta G_{H^-}}) \end{aligned} $$

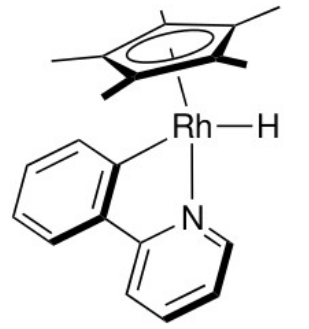

The quantities describing the reactions (BDFE, $\mathrm{\Delta G_{H^-}}$) can be calculated from tabulated $\mathrm{pK_a}$ values and standard reduction potentials. We consider the following example and determine the dominant reaction:

where we have $\ce{Rh(III)}$ with $6$ d-electrons and an electron count of $18.$ For calculating the free energy differences of the $\ce{M-H}$ bond cleavage, we use the tabulated values for the complex:

$$ \begin{aligned} \mathrm{pK_a} &= 30.3 \, (\ce{CH3CN}) \\ \mathrm{E^{\circ}\ce{[Rh(I)/Rh(II)]}} &= -1.85 \, \mathrm{V} \, (\ce{CH3CN}) \\ \mathrm{E^{\circ}\ce{[Rh(II)/Rh(III)]}} &= -1.20 \, \mathrm{V} \, (\ce{CH3CN}) \\ \mathrm{E^{\circ}\ce{[H^+/H^.]}} &= 52.6 \, \mathrm{kcal \, mol^{-1}} \\ \mathrm{E^{\circ}\ce{[H^./H^-]}} &= 26.0 \, \mathrm{kcal \, mol^{-1}} \end{aligned} $$

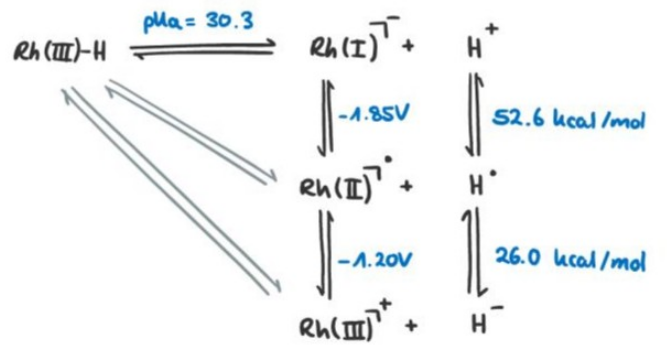

Writing down the reactions in a commutative diagram

and using the conversion constants (which are can be derived from the Nernst equation, using standard conditions):

$$ \begin{aligned} 1 \, \mathrm{pK_a} &\equiv 1.364 \, \mathrm{kcal \, mol^{-1}} \\ 1 \, \mathrm{V} &\approx 23.06 \, \mathrm{kcal \, mol^{-1}} \end{aligned} $$

lets us set up the equations for the free energy differences:

$$ \begin{aligned} \mathrm{\Delta G_{H^+}} &= 1.364 \, \mathrm{kcal \, mol^{-1}} \cdot \mathrm{pK_a} &\approx 41.3 \, \mathrm{kcal \, mol^{-1}} \\ \mathrm{\Delta G_{H^.}} &= \mathrm{\Delta G_{H^+}} + 23.06 \, \mathrm{kcal \, mol^{-1} \, V^{-1}} \cdot \mathrm{E^{\circ}\ce{[Rh(I)/Rh(II)]}} + \mathrm{E^{\circ}\ce{[H^+/H^.]}} &\approx 51.3 \, \mathrm{kcal \, mol^{-1}} \\ \mathrm{\Delta G_{H^-}} &= \mathrm{\Delta G_{H^.}} + 23.06 \, \mathrm{kcal \, mol^{-1} \, V^{-1}} \cdot \mathrm{E^{\circ}\ce{[Rh(II)/Rh(III)]}} + \mathrm{E^{\circ}\ce{[H^./H^-]}} &\approx 49.6 \, \mathrm{kcal \, mol^{-1}} \end{aligned} $$

As the $\mathrm{\Delta G_{H^+}}$ is the lowest, the complex would prefer to lose a proton over a hydride or a hydrogen atom. We can see that even though it's a metal hydride, the complex is more acidic than hydritic.

Considering the trends learnt in the lecture, we can also predict the reactivity of the corresponding complex where the $\ce{Rh}$ is replaced by $\ce{Co}:$

- The complex would become more acidic, as the electrons are more drawn towards the metal due to its higher electronegativity.

- The $\ce{M-H}$ bond becomes weaker, as the metal is less polarizable (same group, but smaller period).

- The complex is less hydritic, the inverse to the first point.

Pd-catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions

Palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions are a powerful tool in organic synthesis. They allow the formation of carbon-carbon bonds under mild conditions:

$$\ce{R-X + R'-M ->[Pd-cat] R-R' + X-M}$$

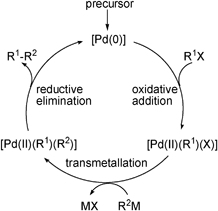

From OCII we remember the general mechanism of such a reaction:

In ACIII we now aim to understand the elementary steps in detail and get an intuition for how we could tune the reaction.

Oxidative Addition (OA)

In an oxidative addition, the metal center of a complex is oxidized by the addition of a ligand. The general reaction is:

$$ \ce{[L_nM^{n+}] + R-X -> [L_nM^{(n+2)+}(R)(X)]} $$

Requirements for OA:

- As the d-electron count is reduced by two, the metal must have d-electrons available.

- The valence electron count of the metal must be below 18, so there is a driving force for the reaction.

- There must be an open coordination site on the metal.

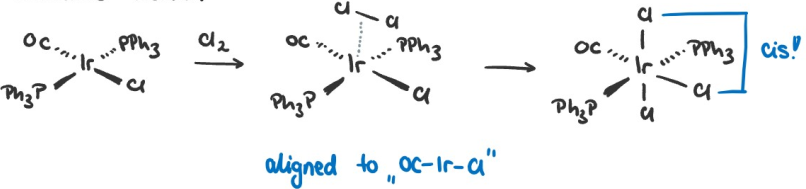

Oxidative additions usually occur over an intermediate, which we want to illustrate with the following examples:

Due to the electron density clash (discussed in Lecture 5), the $\sigma$-complex forms with $\ce{Cl2}$ parallel to the $\ce{OC-Ir-Cl}$ bond. Alternatively we can explain it by analyzing the stabilization effects through $\pi$-backbonding. The triphenylphosphine ($\ce{PPh3}$) ligands are strong $\pi$-acceptors while the $\ce{Cl}$ ligand is a $\pi$ donor. Aligning the $\ce{Cl2}$ ligand parallel to the $\ce{OC-Ir-Cl}$ leaves more electron density in the d-orbital that donates electrons into the $\sigma^{\ast}$-orbital of $\ce{Cl2}$ than if the $\ce{Cl2}$ ligand was aligned parallel to the $\ce{PPh3-Ir-PPh3}$ bond, which is why the shown intermediate is favored.

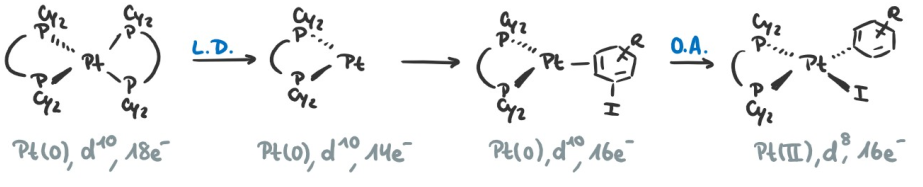

The coordination of the $\pi$ bond is more favorable than the $\sigma$ bond, as the $\pi^{\ast}$ orbitals are lower in energy than the $\sigma^{\ast}$ orbitals $\Rightarrow$ better overlap with the metals d-orbitals. Therefore we observe a different intermediate than in the first example.

Trends in OA

- The more electron-rich the metal, the faster the OA $\Rightarrow$ Replacing $\ce{PPh3}$ with $\ce{PF3}$ would slow down the reaction.

- The lower in energy the $\sigma^{\ast}$ orbitals of the bond that needs to be cleaved, the faster the OA $\Rightarrow$ Replacing $\ce{Ph-I}$ with $\ce{Ph-Cl}$ would slow down the reaction.

- The more sterically demanding the ligands, the slower the OA $\Rightarrow$ Replacing $\ce{PPh3}$ with $\ce{PCy3}$ would slow down the reaction.

C-H vs. Ar-X OA

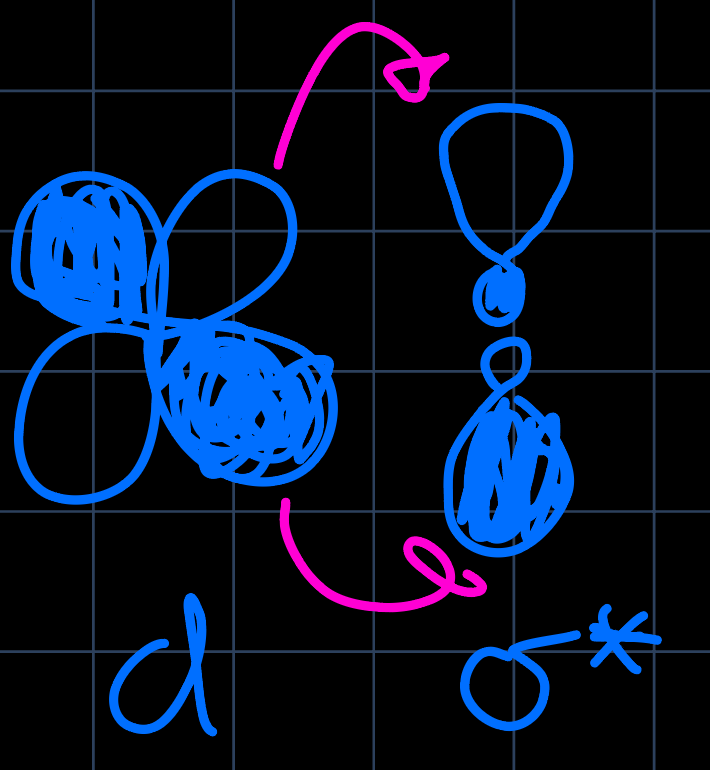

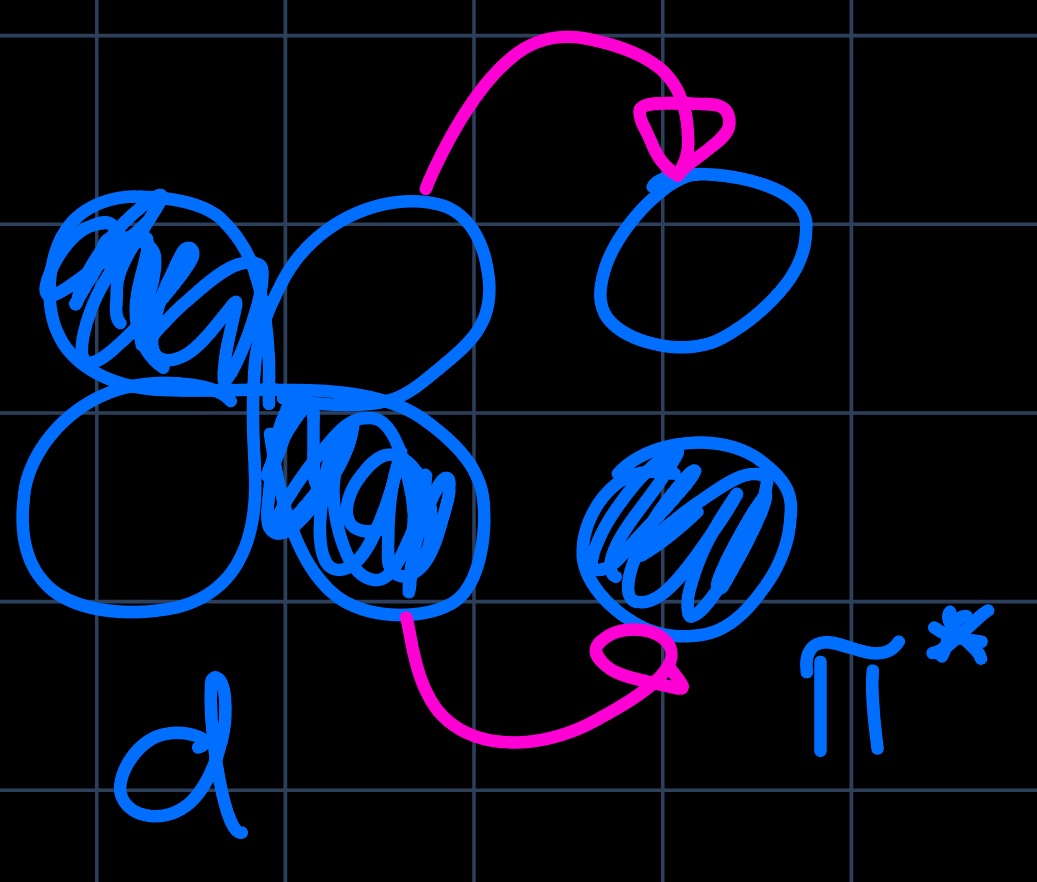

The $\ce{C-H}$ OA proceeds through a different intermediate than the $\ce{Ar-X}$ OA. In the $\ce{C-H}$ OA, the intermediate consists of a $\sigma$-complex, while in the $\ce{Ar-X}$ OA, the intermediate consists of a $\pi$-complex, for which the orbital interactions are shown in the following pictures:

Because the $\sigma^{\ast}$ orbitals lie higher in energy than the $\pi^{\ast}$ orbitals (which lie still higher in energy than the metal d-orbitals), the overlap is much better for the $\eta^2$-complex than for the $\sigma$-complex. The difference even shows up in the rate law by changing the rate-determining step (RDS):

Transmetalation (TM)

This step can be a bit more complex, but it will be covered in the coming weeks.

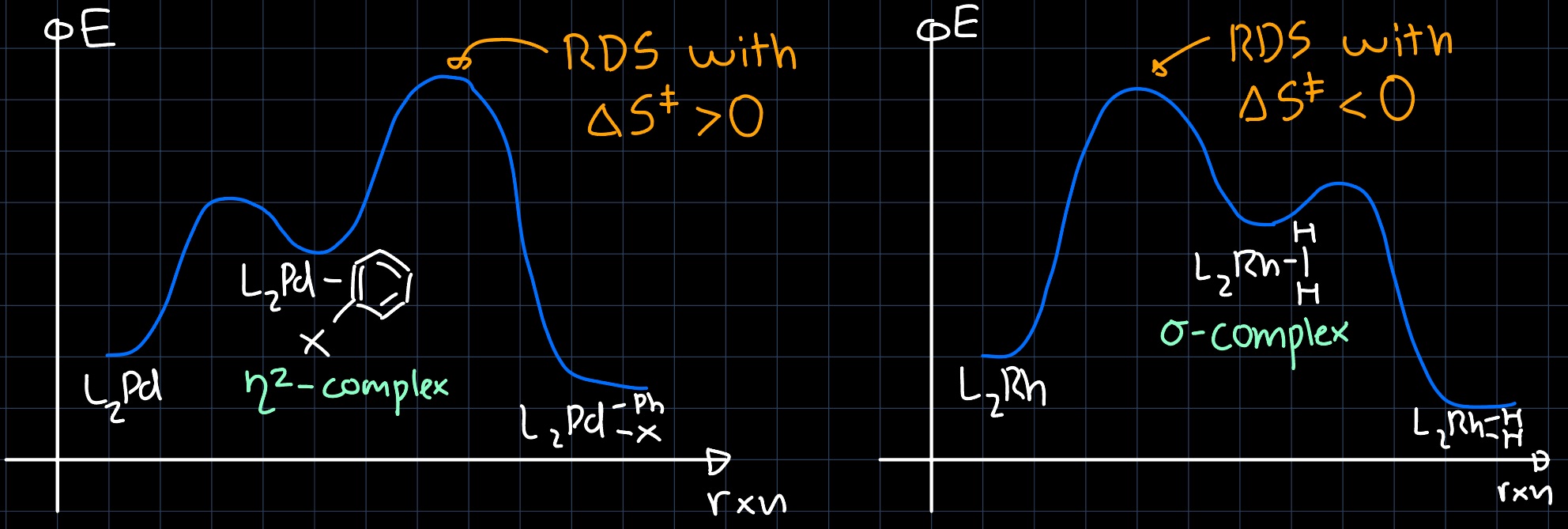

Reductive Elimination (RE)

Reductive eliminations can be considered the reverse reactions to oxidative additions: The metal center of a complex is reduced by the removal of two ligands. The general reaction is:

$$ \ce{[L_nM^{(n+2)+}(R)(X)] -> [L_nM^{n+}] + R-X} $$

The trends in RE are the inverse of OA and we will discuss them based on the following example:

Trends in RE

- The more electron-poor the metal, the faster the RE $\Rightarrow$ Replacing $\ce{Pt}$ by $\ce{Pd}$ would speed up the reaction.

- The bulkier the ligands, the faster the RE $\Rightarrow$ Replacing $\ce{PPh3}$ with $\ce{PCy3}$ would speed up the reaction.

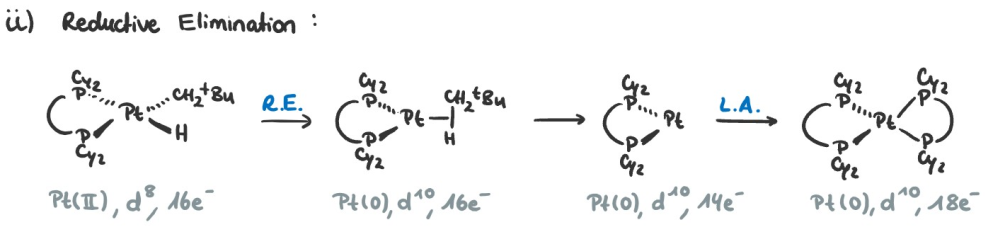

(Inverse) Kinetic Isotope Effects

If replacing an atom in one of the reactants by another of its isotopes results in a change of the reaction rate, we speak of a KIE. Exploitation of the kinetic isotope effect (KIE) can be a powerful tool for elucidation of reaction mechanisms.

In the lecture, the KIE was explained based on different zero-point energies of the harmonic oscillator model for bonds between different isotopes of the same elements. Based on the same principle we can use the following equation describing the wave-number of a harmonic oscillator:

$$ \tilde \nu = \frac{1}{2\pi c} \sqrt{\frac{k}{\mu}} $$

where $k$ is the force constant of the bond, which we assume to remain constant for the isotopes, and $\mu$ is the reduced mass of the two atoms. Comparison of a $\ce{C-H}$ bond with a $\ce{C-D}$ bond and using $\mu = \frac{m_1 m_2}{m_1 + m_2}$ gives

$$ \frac{\mu_{\ce{D}}}{\mu_{\ce{H}}} \approx 2 \Rightarrow \tilde \nu_{\ce{C-D}} \approx \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \tilde \nu_{\ce{C-H}} $$

This implies that the $\ce{C-D}$ is stronger and thus requires a higher activation energy to be broken $\Rightarrow$ reactions breaking the $\ce{C-D}$ bond are slower, explaining the normal KIE $\frac{k_{\ce{C-H}}}{k_{\ce{C-D}}} > 1.$

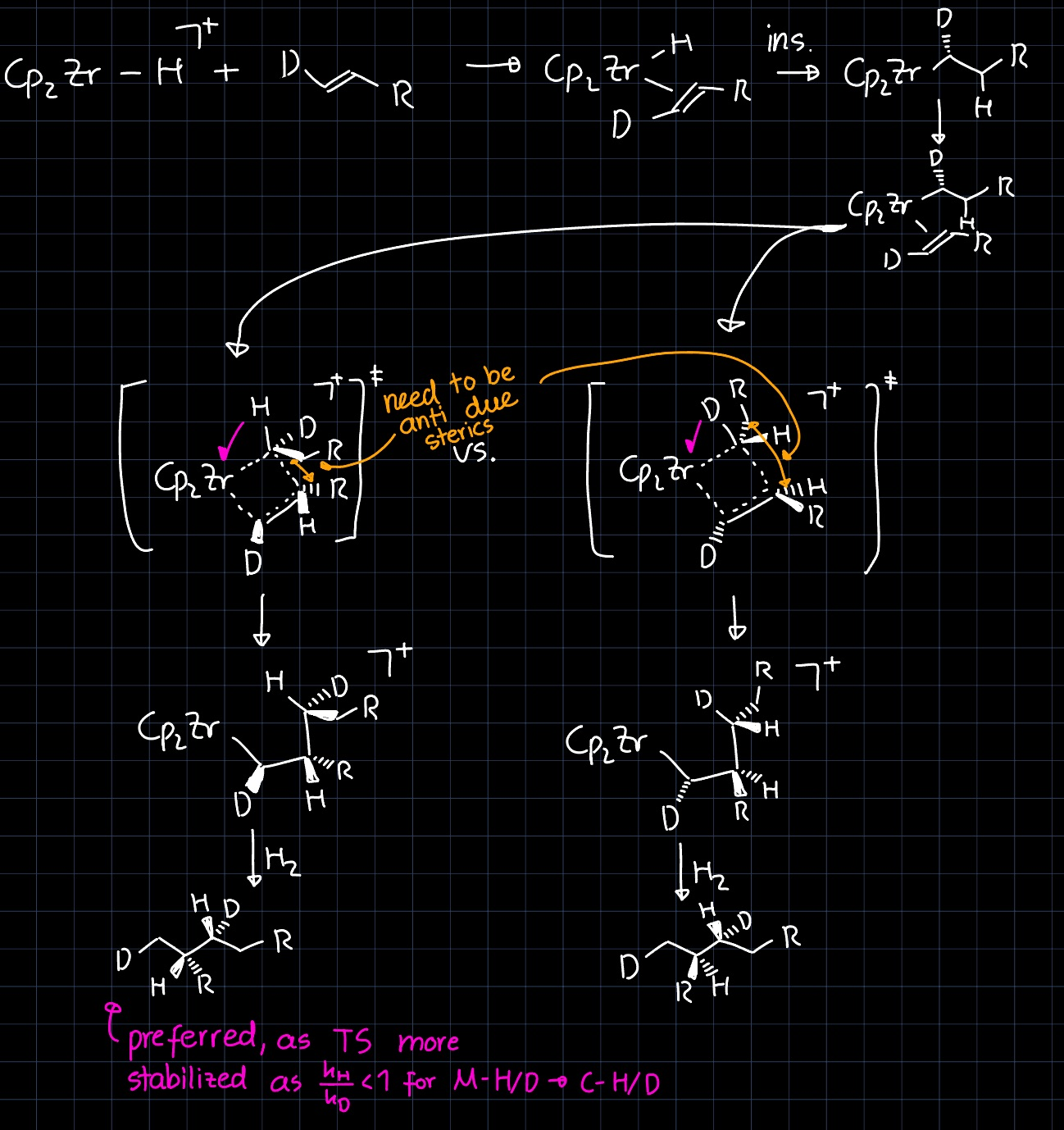

However, in some cases we observe $\frac{k_{\ce{C-H}}}{k_{\ce{C-D}}} < 1,$ which is called an inverse KIE. For metal hydrides this can be explained by remembering that the $\ce{M-H}$ bond is much weaker than the $\ce{C-H}$ bond, so the difference in bond strength of the reactant ($\ce{M-H/D}$) is less than the difference in bond strength of the product ($\ce{C-H/D}$). Following Hammond's postulate, the difference in bond strength should be more pronounced in the transition state, resulting in a higher activation energy for the heavier isotope than for the lighter and thus a lower rate. Considering the reaction coordinate diagram we get the following picture (left normal KIE, right inverse KIE):

Elementary Steps in Organometallic Chemistry

Topics Covered

- Oxidative Addition

- Reductive Elimination

- $\sigma$-Bond Metathesis

- (Migratory) Insertion and $\beta$-Hydride Elimination

Oxidative Addition

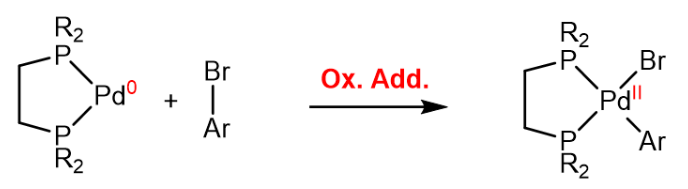

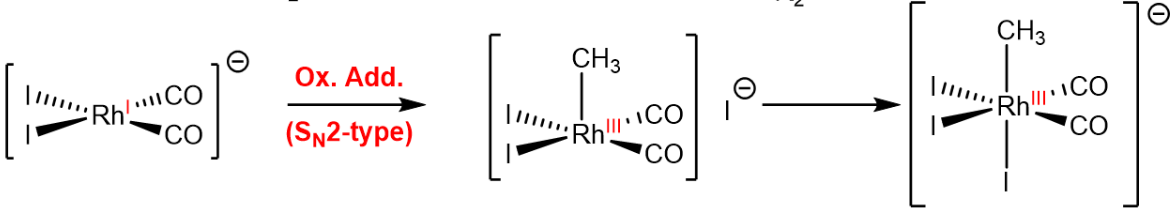

In the oxidative addition, the metal center is oxidized by inserting into a sigma bond, which leads to an increase in the coordination number of the metal center, a decrease of the d-electron count by two (as the oxidation state is increased by two) and an increase of the valence electron count by two, as two new $\ce{M-L}$ bonds are formed. Two examples are provided below.

Reductive Elimination

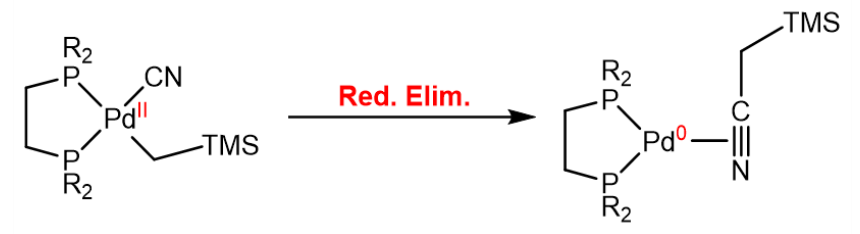

In the reductive elimination, the metal center is reduced by eliminating a two ligands, which leads to a decrease in the coordination number of the metal center, an increase of the d-electron count by two (as the oxidation state is decreased by two) and a decrease of the valence electron count by two, as two $\ce{M-L}$ bonds are broken:

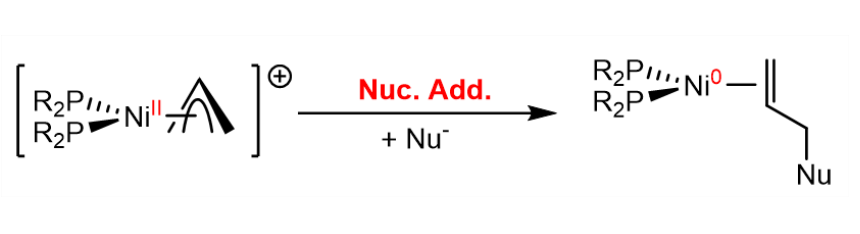

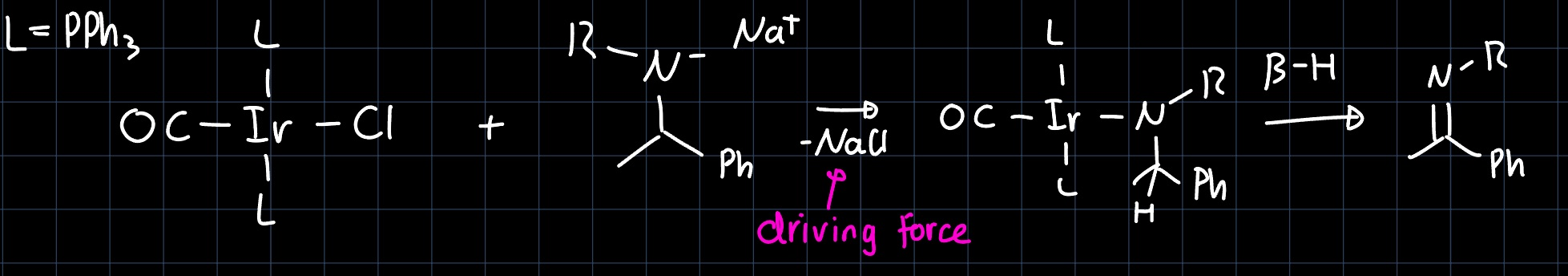

A reductive elimination can also be induced by a nucleophilic attack on a ligand coordinated to tbe metal center:

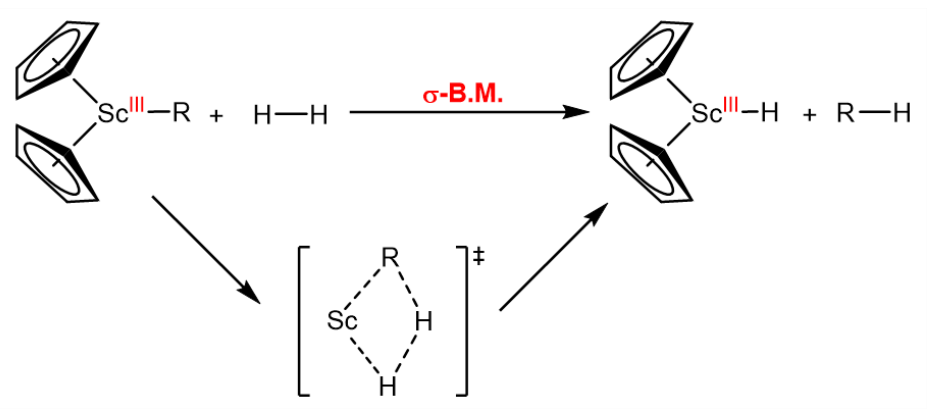

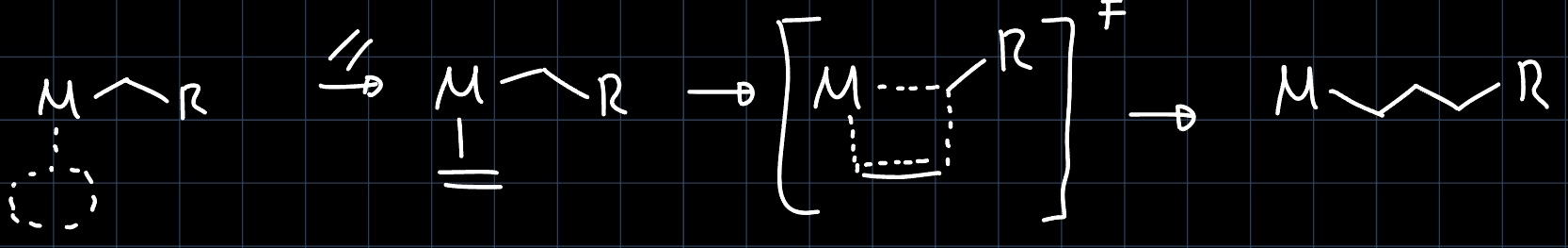

$\sigma$-Bond Metathesis

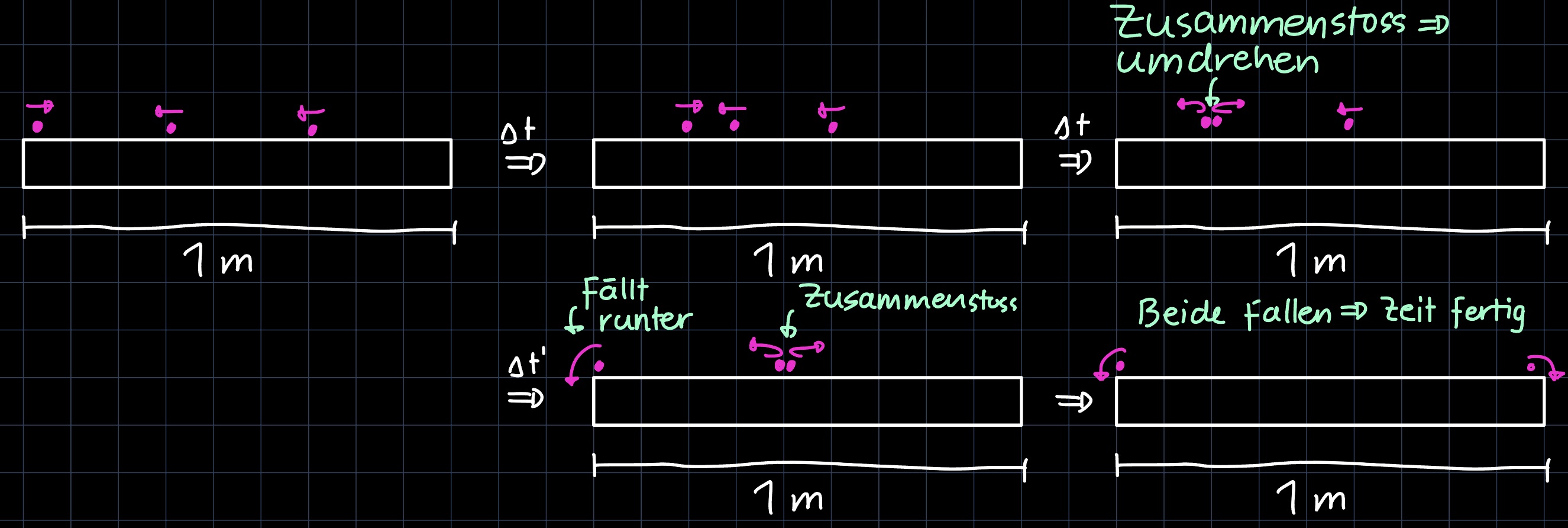

$\sigma$-Bond metathesis allows for the exchange of alkyl ligands and the formation of $\ce{M-C}$ bonds. The reaction is very important in organometallic chemistry, as it opens the door to hydrocarbon functionalization, serving as a tool to convert feedstock chemicals ($\ce{CH4}$, $\ce{C2H6}$, $\ce{C3H8}$, $\ce{C4H10}$, $\dots$) into value-added chemicals. The reaction proceeds through a cyclic "orbitally continuous" transition state, which is a hallmark of the reaction:

Insertion and $\beta$-Hydride Elimination

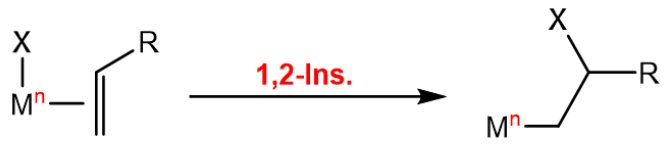

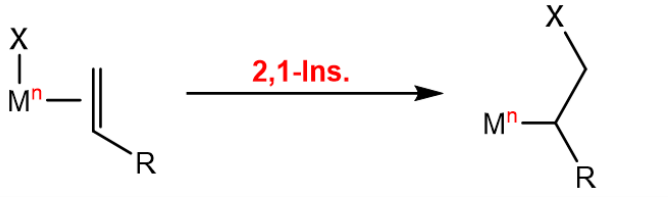

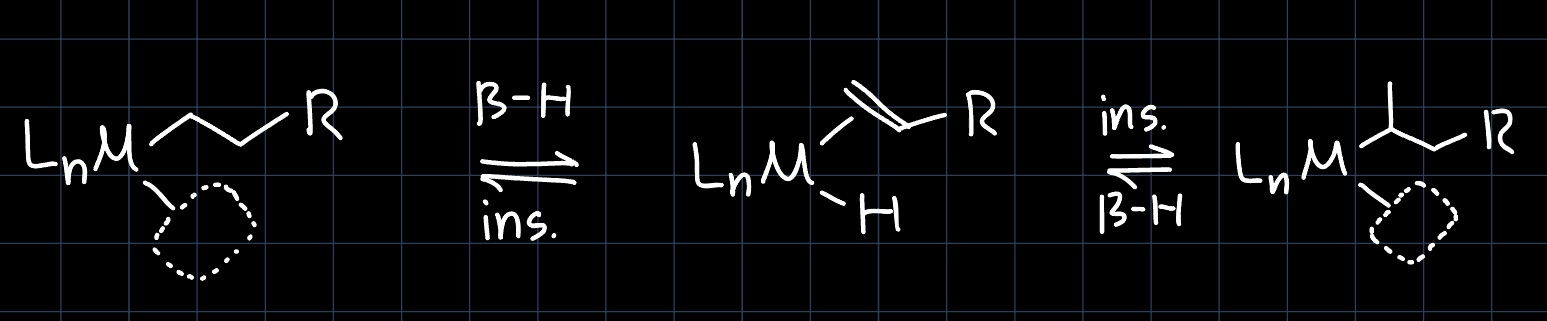

In organometallic chemistry, insertion reactions refer to the insertion of a ligand into the double bond of an olefin which is also coordinated to the metal center. This opens up a coordination site, where another olefin can coordinate, making it the key reaction in olefin polymerization. As the olefin is not necessarily symmetric around the double bond, the insertion can lead to two different products, depending on which way it is oriented:

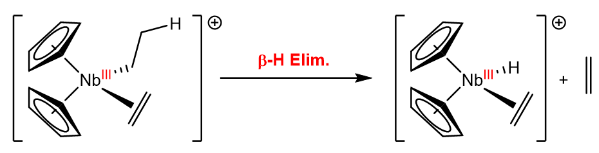

The $\beta$-hydride elimination is the reverse of the insertion reaction, where a hydride is eliminated from the metal center, and the olefin is formed:

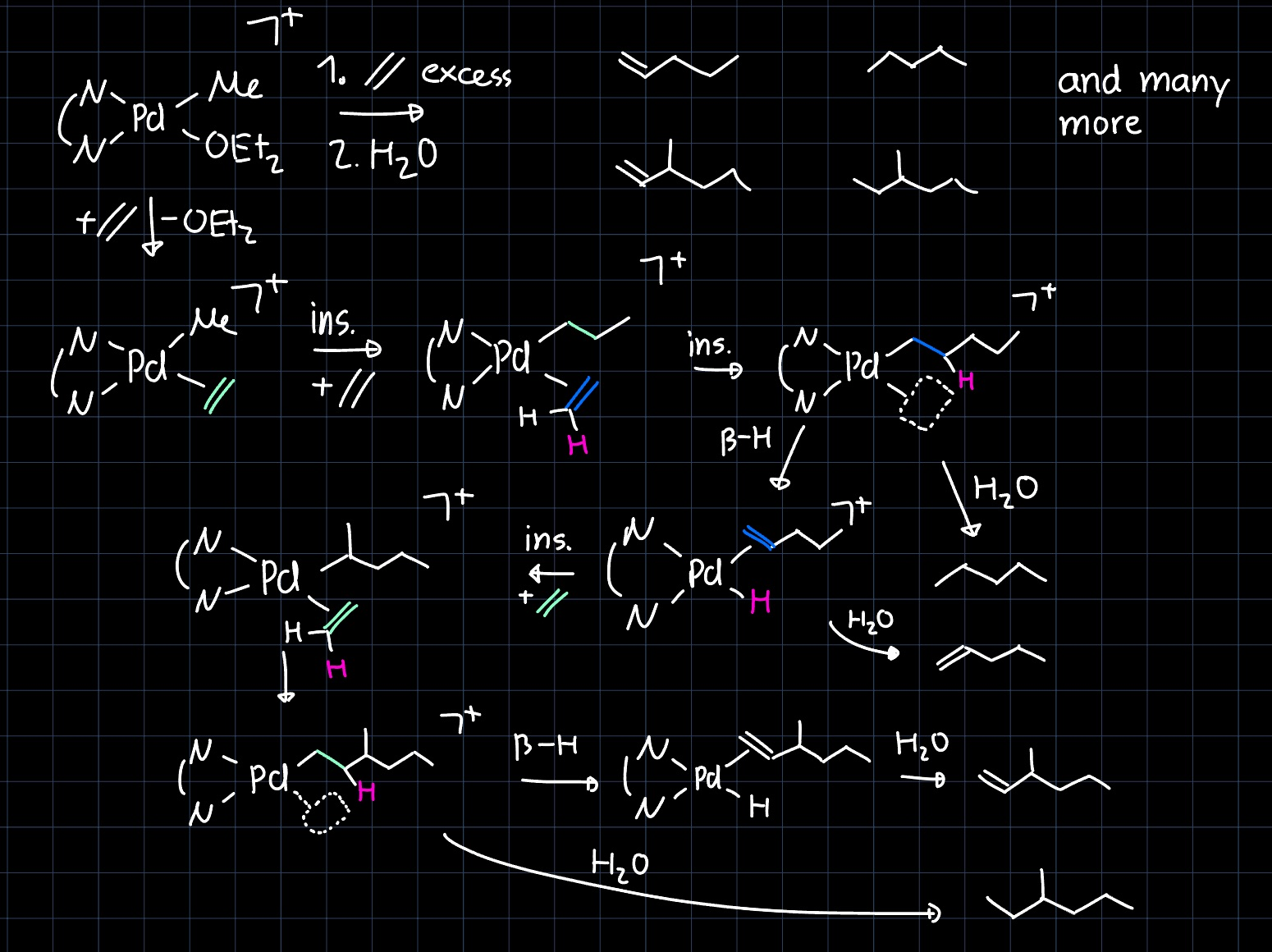

To understand how this impacts polymerization reactions, let us consider an example which shows how different products can be formed depending on the way the olefin is inserted:

$\beta$-Hydride elimination can also happen for functionalized alkyl ligands that coordinate to the metal center over a heteroatom:

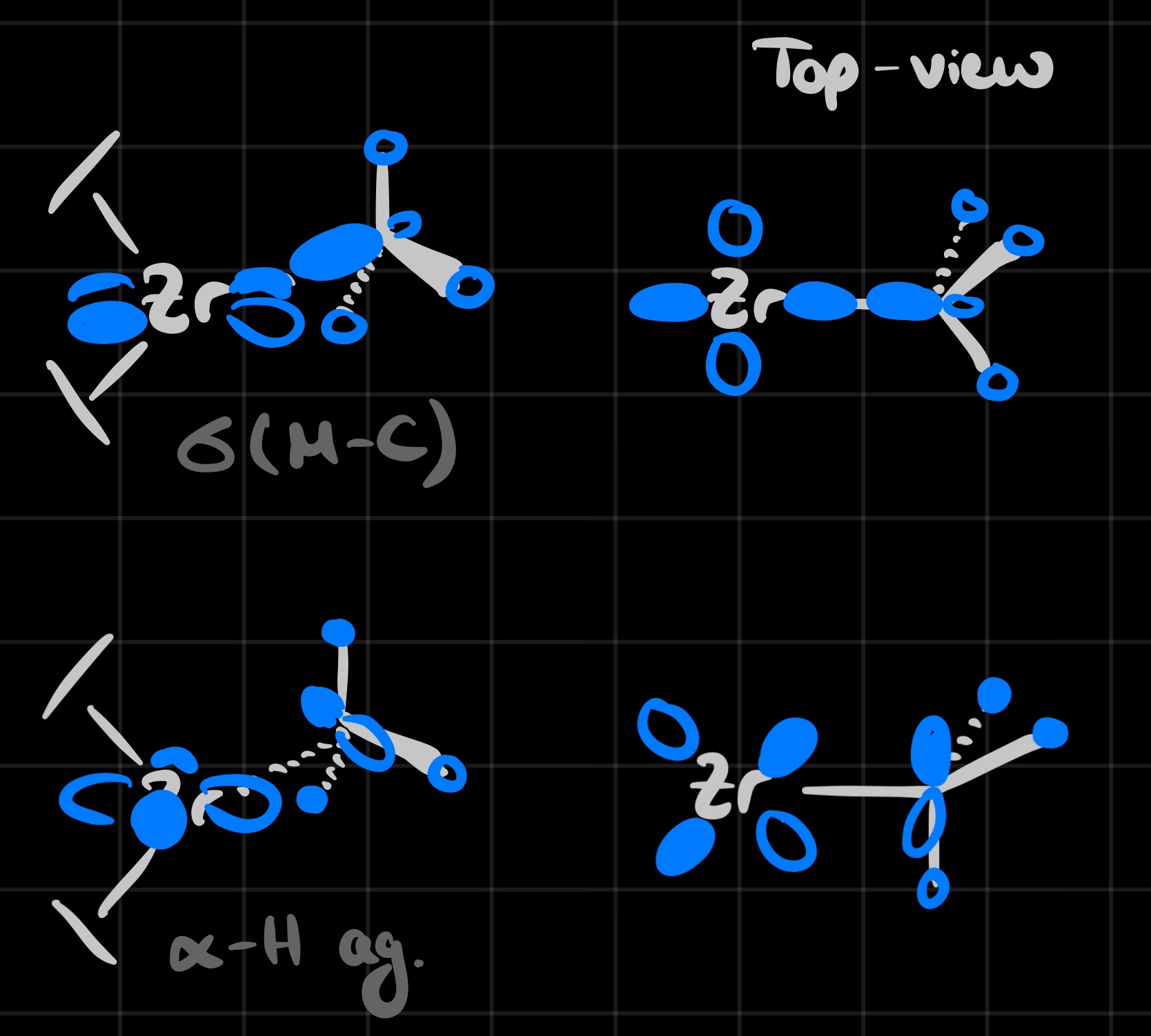

Mechanism of the Insertion Reaction

For the mechanism of the olefin insertion, we have discussed two limiting cases: In the Cassee-Arlman (CA) mechanism, the olefin coordinates to the metal center, and inserts into an existing metal alkyl bond in a concerted fashion:

This however, cannot describe the mechanism accurately, as the only requirement to the metal complex would be an open coordination site for the olefin, which many species would satisfy, that don't show this behavior.

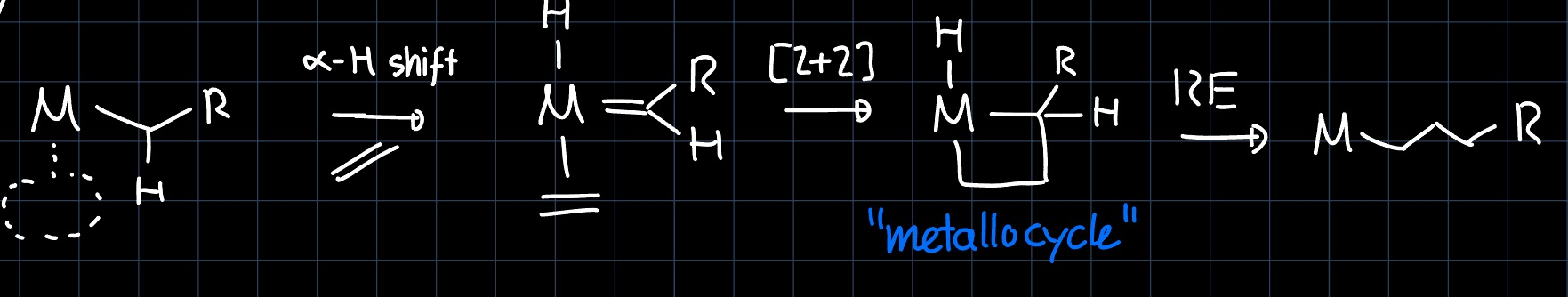

The other limiting case is the Green-Rooney (GR) mechanism, where before the reaction an $\alpha$-hydride is shifted from the alkyl ligand to the metal, paving the way for a $[2+2]$ cycloaddition. The insertion is then completed by a $\ce{CH}$ reductive elimination which opens up the metallocycle:

The problem with this mechanism is that the $\alpha$-hydride shift requires a d-electron count of at least two, which is not true for example for $\ce{Cp^*_2Lu-CH3}$, which is known to carry out olefin polymerization.

The actual mechanism is a combination of both, where the $\alpha$-hydride shift only partially happens through a so-called $\alpha$-agostic interaction:

The interaction weakens the $\alpha-\ce{C-H}$-bond and strengthens the $\ce{M-C}$-bond. Through that some requirements are imposed on the electronic structure of the metal, narrowing down the number of complexes that can carry out olefin polymerization, while not ruling out d$^0$ complexes like $\ce{Cp^*_2Lu-CH3}$.

The interaction can be experimentally confirmed by its influence on the diastereoselectivity in the polymerization of isotope labelled olefins:

Trends in Product Formation

Late transition metals (TMs) produce more branched products than early TMs, for them the equilibrium between insertion and $\beta$-hydride elimination is shifted towards the state where the hydride is eliminated. This property arises from the stronger $\pi$-backdonation into the $\ce{C=C}$-bond and the stronger $\ce{M-H}$ bond. Due to the different resting state, both insertion positions are well accessible and branching occurs more likely:

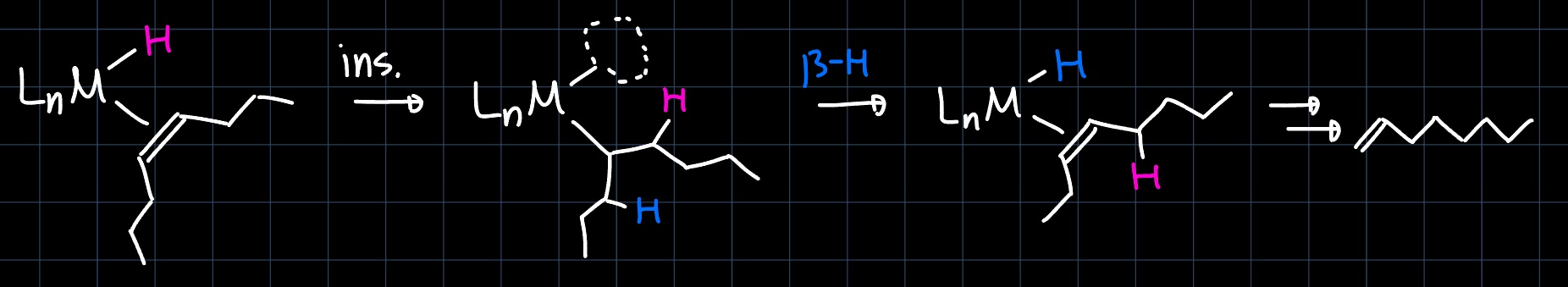

Another phenomena observed by later TM olefin polymerization complexes is that the olefin products have the double bond almost exclusively in terminal position. This happens through successive insertion and $\beta$-hydride elimination steps and is called chain walking:

Basic Orbital Interactions in TM Complexes

Topics Covered

- 18 Electron Rule from Another Perspective

- Orbital Interactions in Transition Metal Complexes

- Stereoselective Catalytic Cycle

18 Electron Rule from Another Perspective

Inorganic chemistry is often taught from the perspective of the 18 electron rule, which is a useful tool to predict the stability of transition metal complexes. However, the rule is only a guideline that can help, but is just as often wrong. It originated from stable octahedral d$^6$ complexes, which exhibit a valence electron count of 18. But e.g. $\ce{Hg}$ usually forms $\ce{HgX2}$ complexes, which have a VEC of just 14 but are stable nevertheless.

Orbital Interactions in Transition Metal Complexes

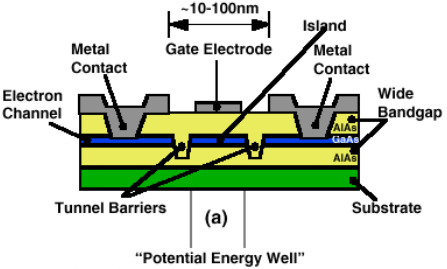

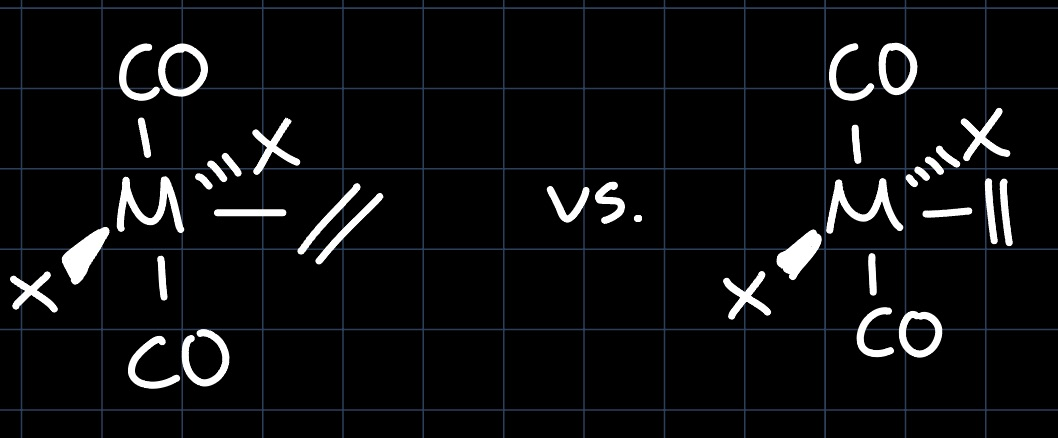

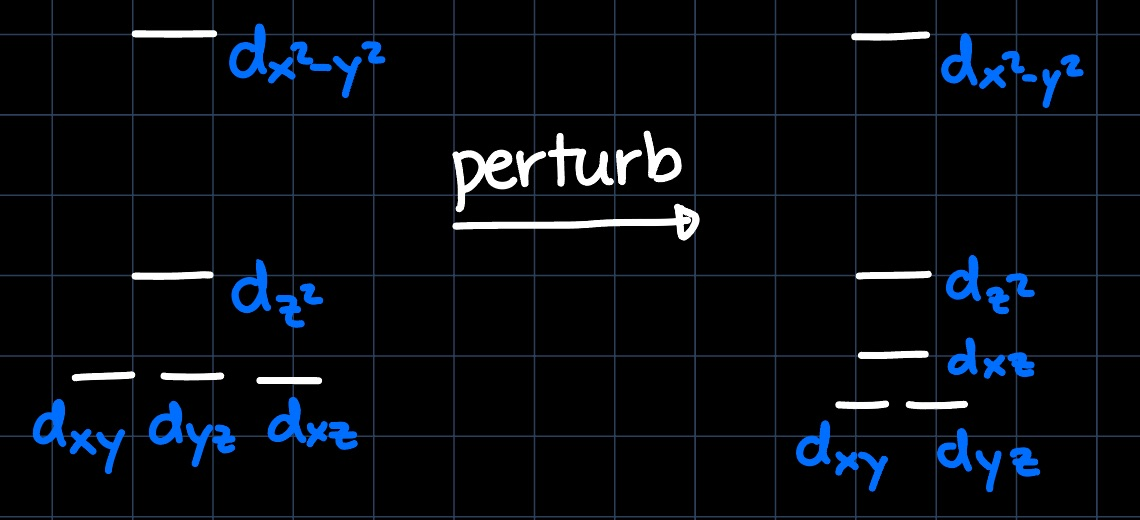

In the lecture we have started with the known molecular orbital (MO) diagram (just the d-block, as only the FMOs are relevant for the reactivity) for an octahedrally coordinated complex and have derived the MO diagram for other geometries by perturbation. However, we have treated all ligands the same and not considered their different $\sigma$-donor and $\pi$-acceptor abilities. To get an idea of what happens, consider the complex $\ce{W(CO)6}$, which can be synthesized by the reduction of $\ce{WCl6}$ with $\ce{CO}$.

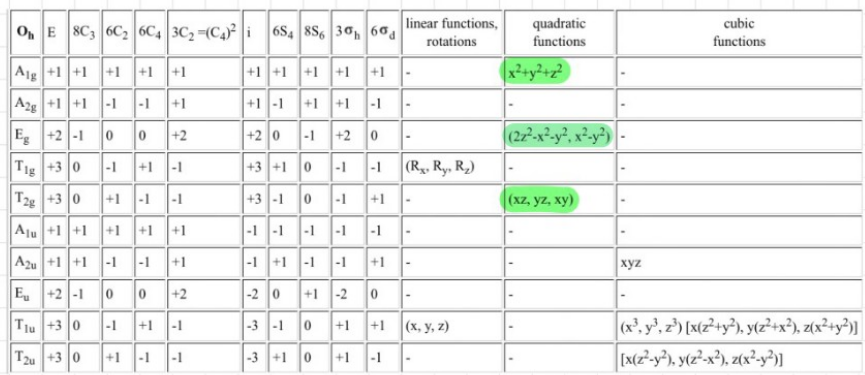

From the character table:

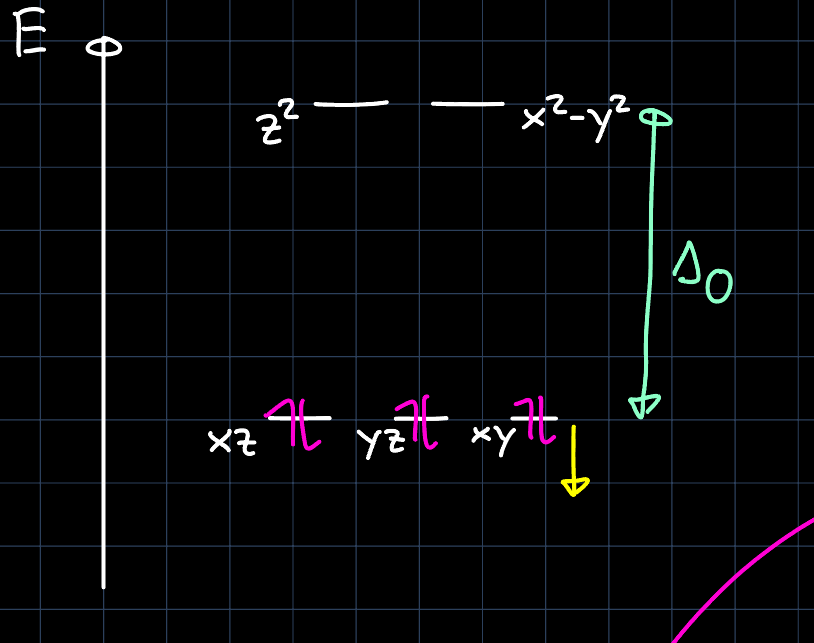

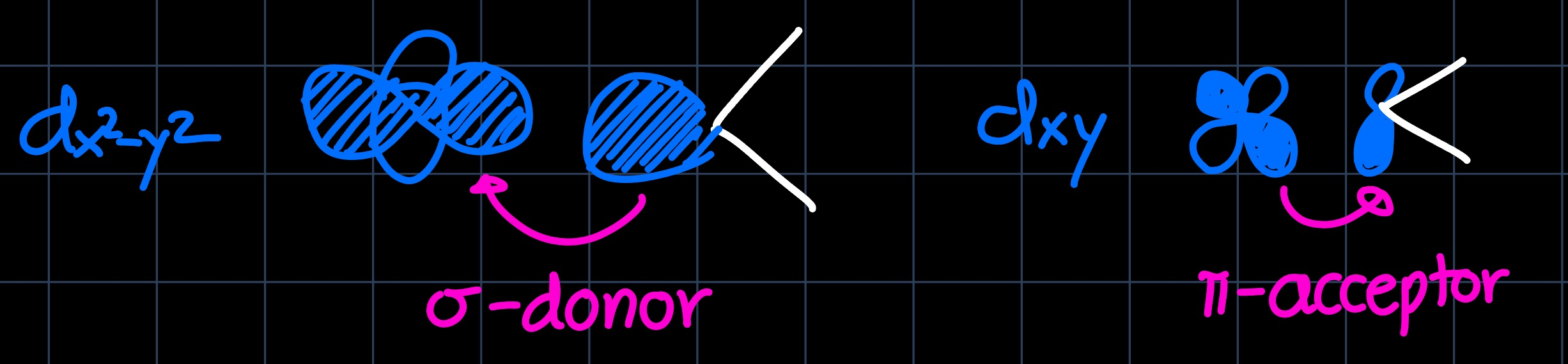

we read that there are two degenerate energy levels for the d-block and either by remembering or drawing the orbital interactions, we can setup the MO diagram for an octahedral complex. This is now perturbed by the nature of the $\ce{CO}$ ligands: They are very strong $\pi$-acceptors, which lowers the $d_{xy}, d_{yz}$ and $d_{xz}$ orbitals in energy as they can interact with the $\pi^{\ast}$ orbitals:

and they are $\sigma$-donors, which elevates the $d_{z^2}$ and $d_{x^2-y^2}$ orbitals in energy as they can interact with the $\sigma$ orbitals:

This results in a larger splitting $\Delta_O$ of the d-block:

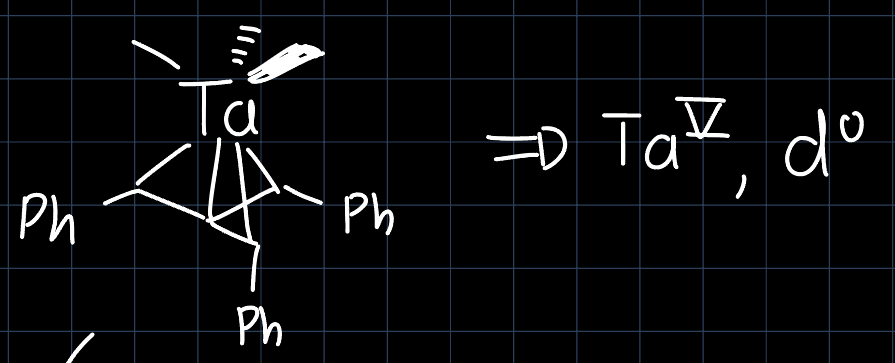

Hexa-coordinated transition metal complexes can also be non-octahedrally coordinated. An example is the (approximately) prismatic Tantalum complex:

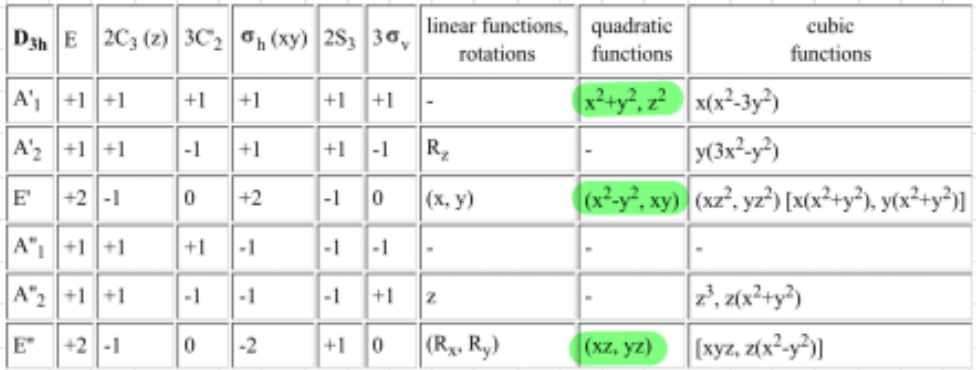

The point group is $D_{3h}$, which has the character table:

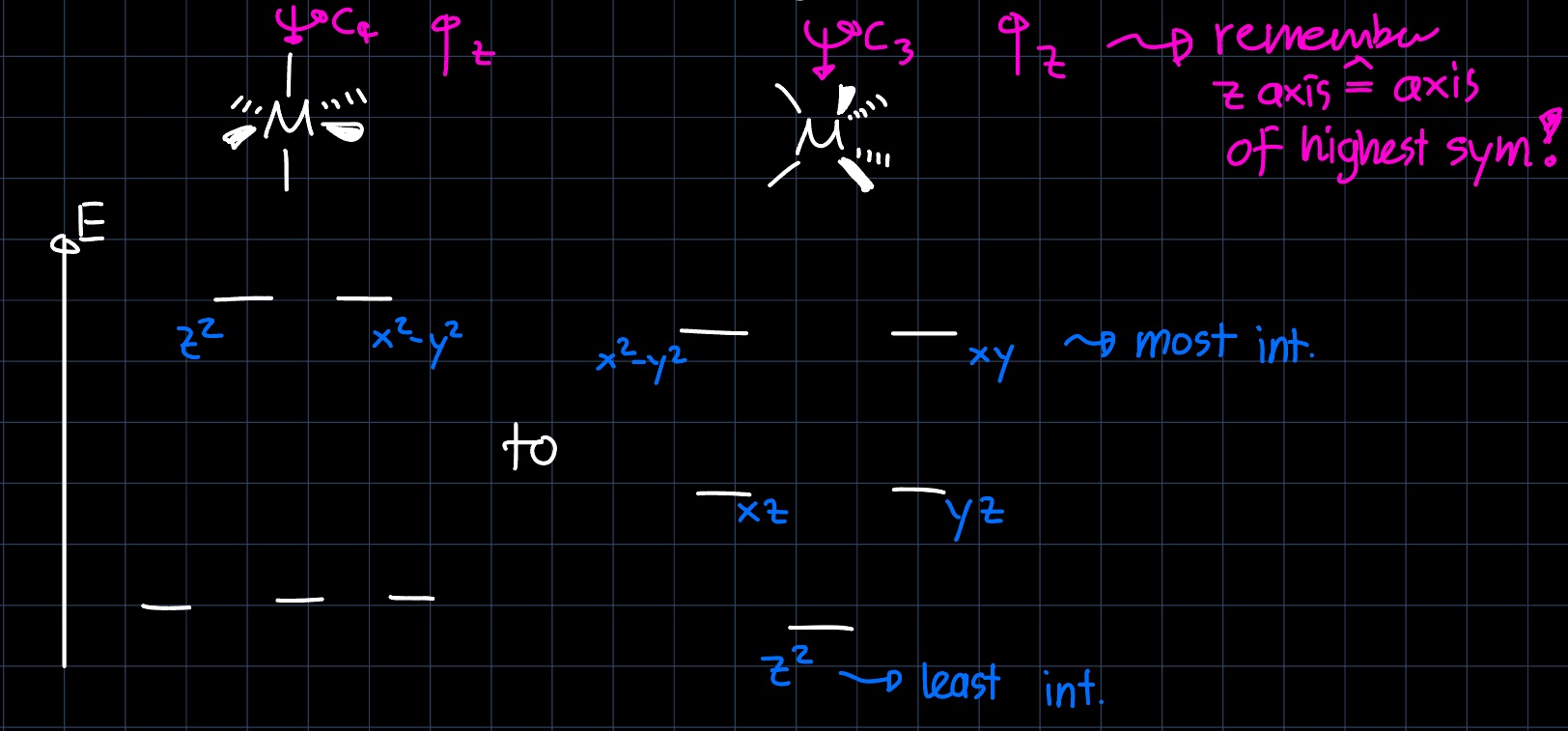

from which we read that there will be three degenerate energy levels for the d-block. The MO diagram is then setup by considering the interactions of the d-orbitals with the ligands to get:

However, as Tantalum is in its highest oxidation state $\ce{Ta^{V}}$, this doesn't explain the curious geometry and also steric effects would suggest octahedral coordination. However we have to remember that there are many more orbitals that are lower in energy and thus filled. Through the distortion of the octahedral structure to the prismatic structure, some filled-filled interaction can be minimized, which makes the prismatic structure energetically more favorable:

Stereoselective Catalytic Cycle

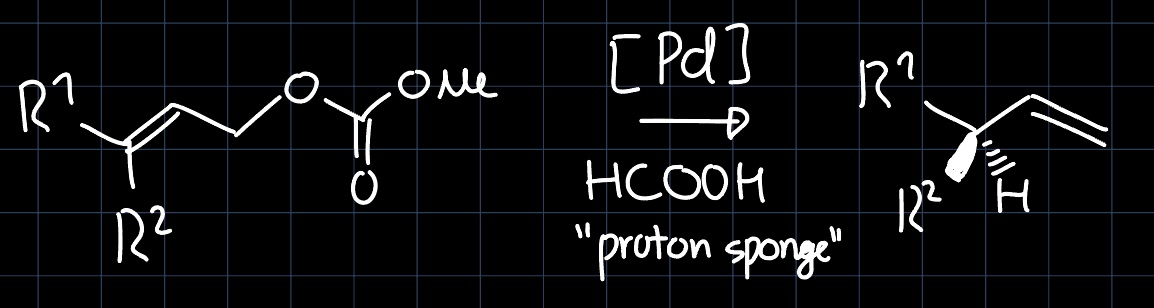

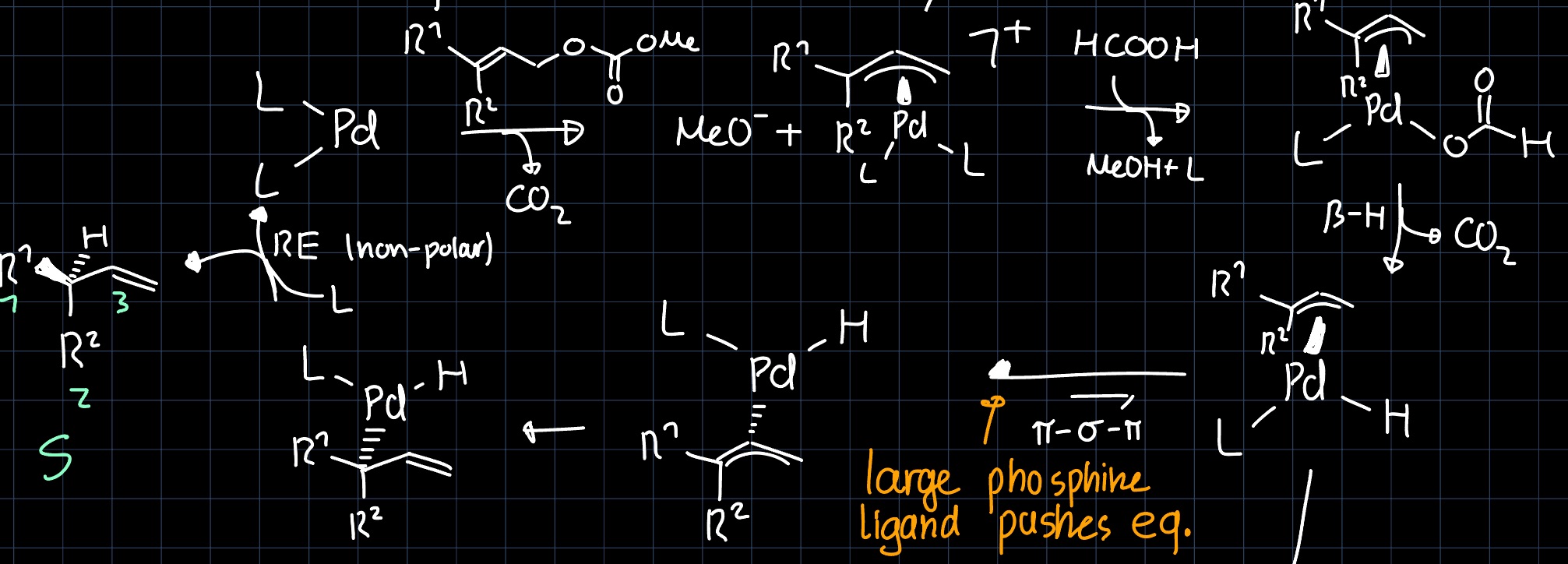

Understanding the orbital structure of transition metal complexes is an important tool in understanding the outcome of stereoselective reactions. Consider the following reaction:

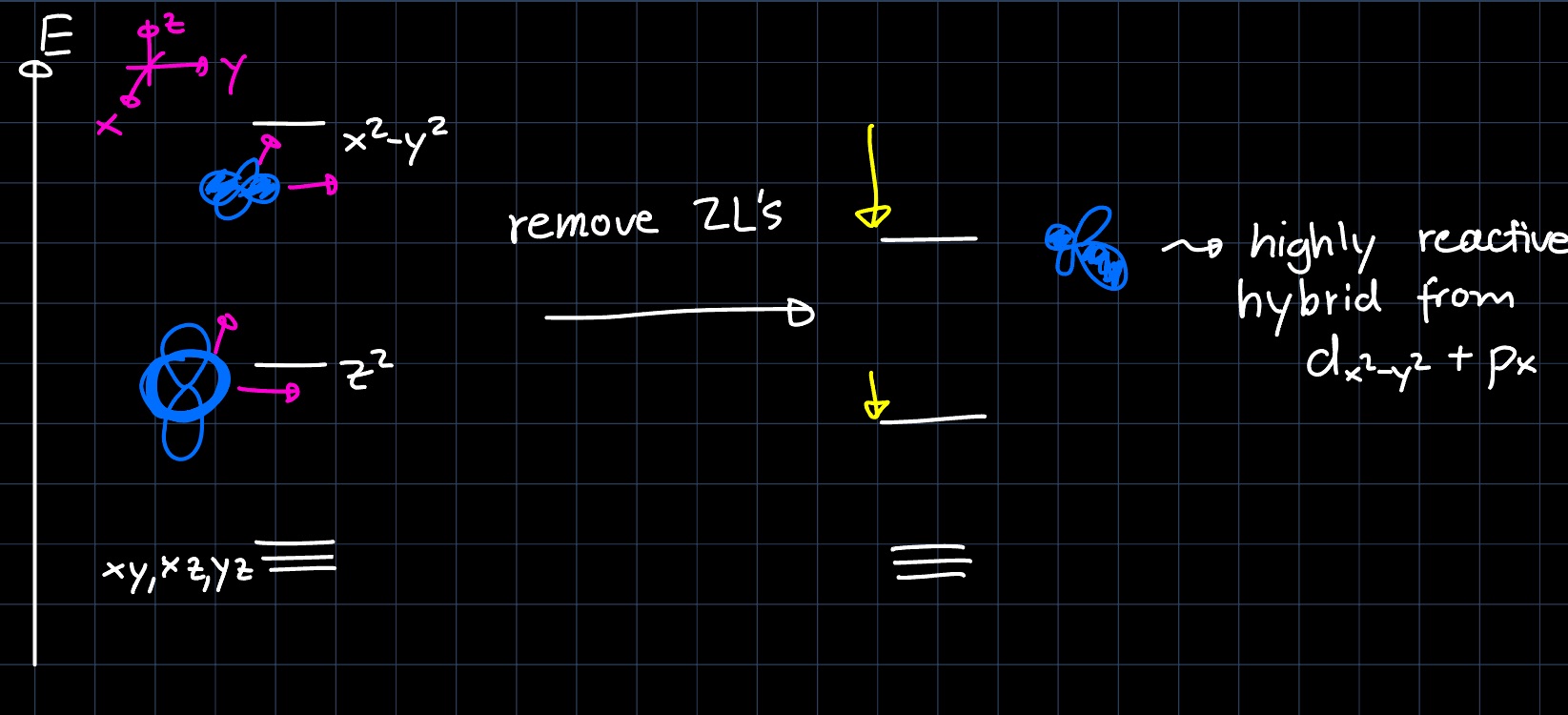

where the palladium complex (catalyst) is setup with a very bulky, chiral ligand and exhibits square planar geometry. First we want to determine the active species that reacts with the allyl (formed from the reactant under $\ce{CO2}$ elimination). Removing two ligands to form an L-shaped intermediate, we can see that only the $d_{x^2-y^2}$ and $d_{z^2}$ are lowered in energy, as the others do not interact. This leads to the following perturbation of the MO diagram:

The $d_{x^2-y^2} + p_x$ hybrid orbital is then highly reactive towards the allyl group and the catalytic cycle can proceed according to the following mechanism:

Metallocenes

Topics Covered

- MO Diagram of Linear Metallocenes

- MO Diagram of Bent Metallocenes

- Structure and Reactivity of Bent Metallocenes

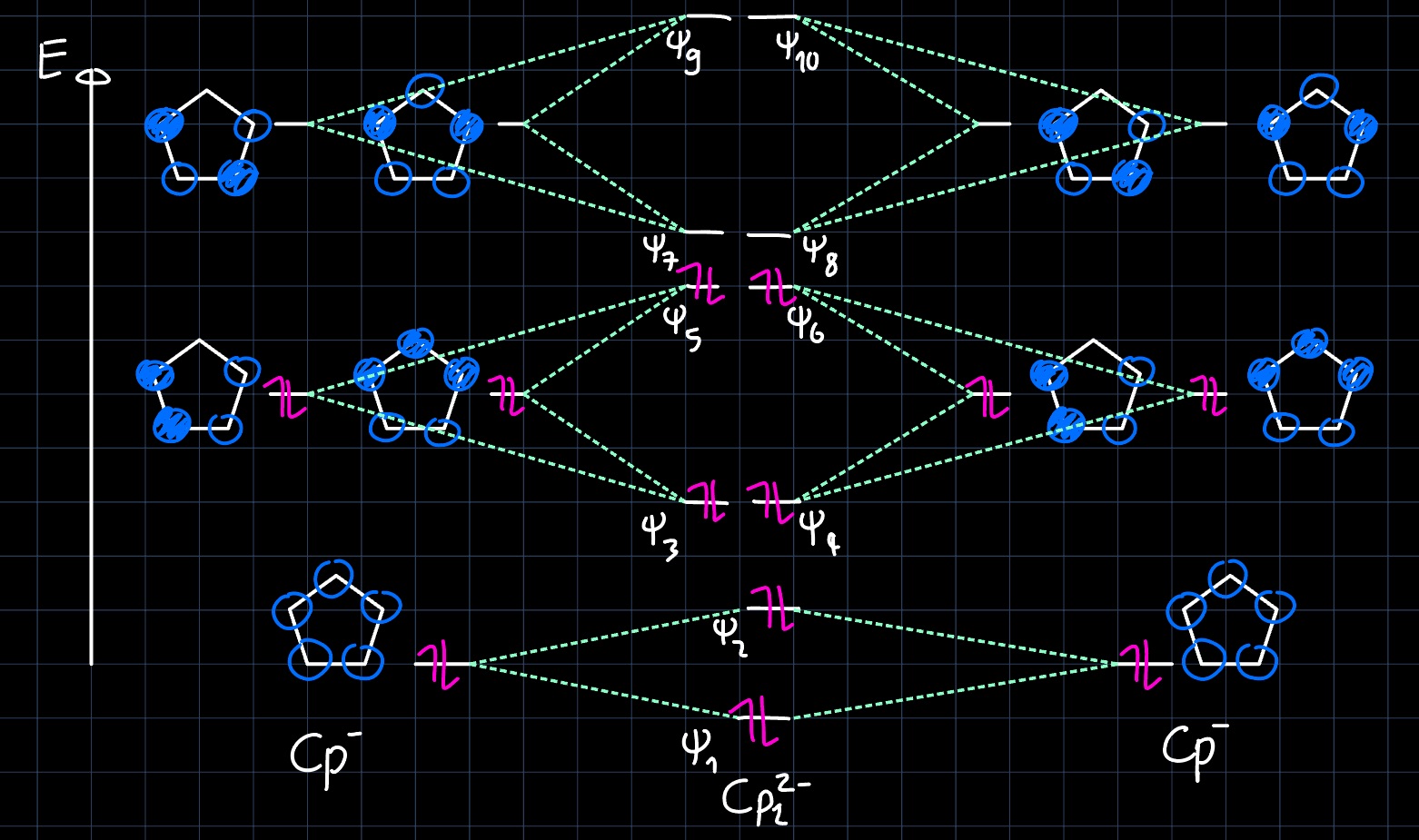

MO Diagram of Linear Metallocenes

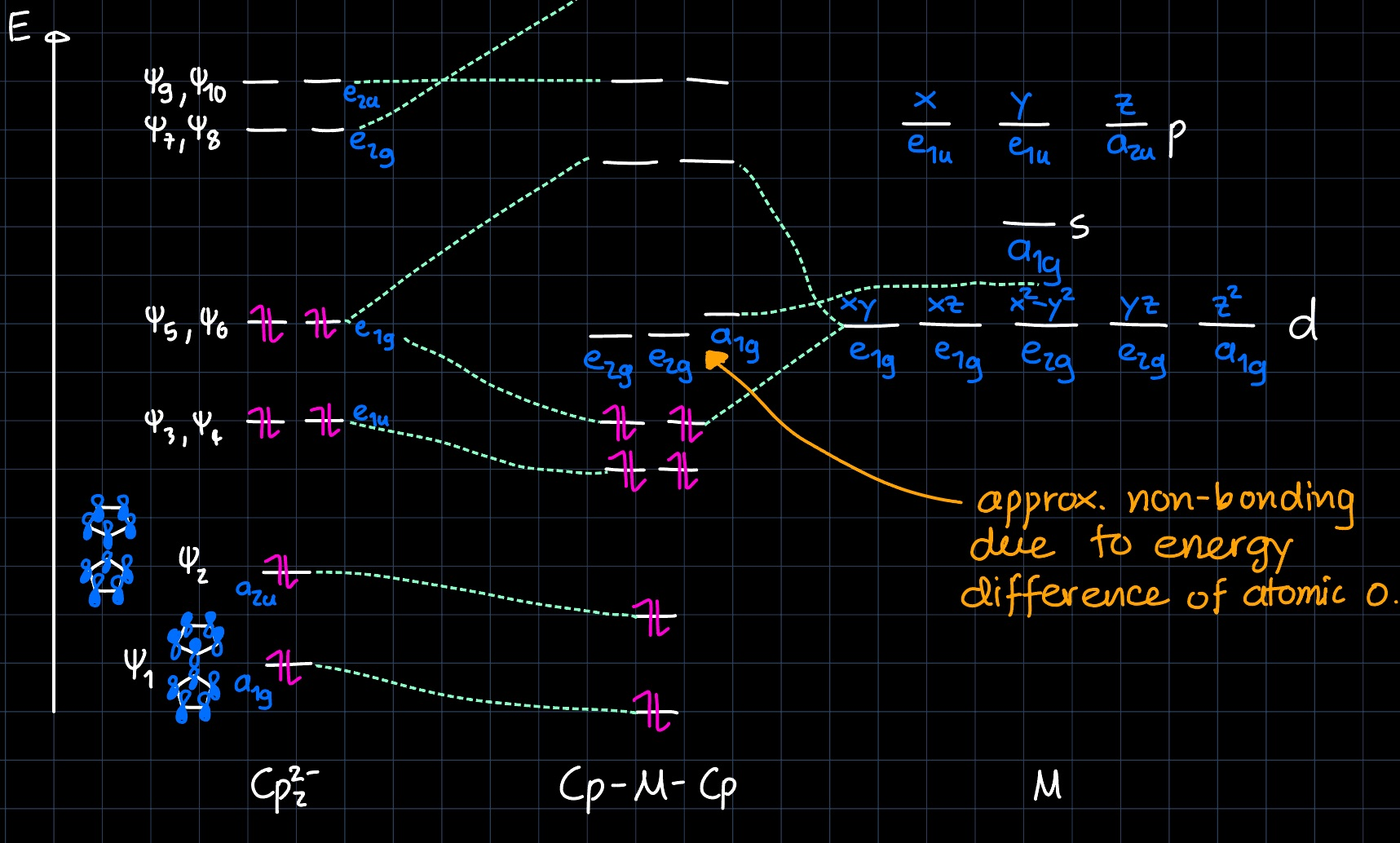

In the lecture Metallocenes, $\ce{Cp2M}$, where $\ce{Cp}$ is the cyclopentadienyl ligand, were discussed. Such compounds are often employed as catalysts in polymer chemistry. In order to gain a better understanding of their reactivity, we will examine the electronic structure through the molecular orbital (MO) diagram. Let's start by setting up the MO diagram for the "superligand" $\ce{Cp2^{2-}}$. From the known MO diagram of $\ce{Cp-}$ and by linear combination of atomic orbitals (LCAO) theory, we get:

where the two $\ce{Cp-}$ are aligned such that there is an inversion center. Due to orbital overlap, the combinations that are symmetric with respect to that inversion center are lowered in energy (bonding), while the antisymmetric combinations are increased in energy (antibonding). Note that this leads to an octahedral-like coordination of the central metal.

The $\ce{Cp2^{2-}}$ superligand can now interact with the metals orbitals, which can best be achieved through examining the character table of the $D_{5d}$ point group:

| D5d | E | 2C5 | 2(C5)2 | 5C'2 | i | 2(S10)3 | 2S10 | $5\sigma_d$ | rotations |

functions |

functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1g | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 | - | x2+y2, z2 | - |

| A2g | +1 | +1 | +1 | -1 | +1 | +1 | +1 | -1 | Rz | - | - |

| E1g | +2 | $+2\cos(\frac{2}{5}\pi)$ | $+2\cos(\frac{4}{5}\pi)$ | 0 | +2 | $+2\cos(\frac{2}{5}\pi)$ | $+2\cos(\frac{4}{5}\pi)$ | 0 | (Rx, Ry) | (xz, yz) | - |

| E2g | +2 | $+2\cos(\frac{4}{5}\pi)$ | $+2\cos(\frac{2}{5}\pi)$ | 0 | +2 | $+2\cos(\frac{4}{5}\pi)$ | $+2\cos(\frac{2}{5}\pi)$ | 0 | - | (x2-y2, xy) | - |

| A1u | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | - | - | - |

| A2u | +1 | +1 | +1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | +1 | z | - | z3, z(x2+y2) |

| E1u | +2 | $+2\cos(\frac{2}{5}\pi)$ | $+2\cos(\frac{4}{5}\pi)$ | 0 | -2 | $-2\cos(\frac{2}{5}\pi)$ | $-2\cos(\frac{4}{5}\pi)$ | 0 | (x, y) | - | (xz2, yz2) [x(x2+y2), y(x2+y2)] |

| E2u | +2 | $+2\cos(\frac{4}{5}\pi)$ | $+2\cos(\frac{2}{5}\pi)$ | 0 | -2 | $-2\cos(\frac{4}{5}\pi)$ | $-2\cos(\frac{2}{5}\pi)$ | 0 | - | - | [xyz, z(x2-y2)] [y(3x2-y2), x(x2-3y2)] |

and assigning the irreducible representation. The most prominent interactions are shown below:

MO Diagram of Bent Metallocenes

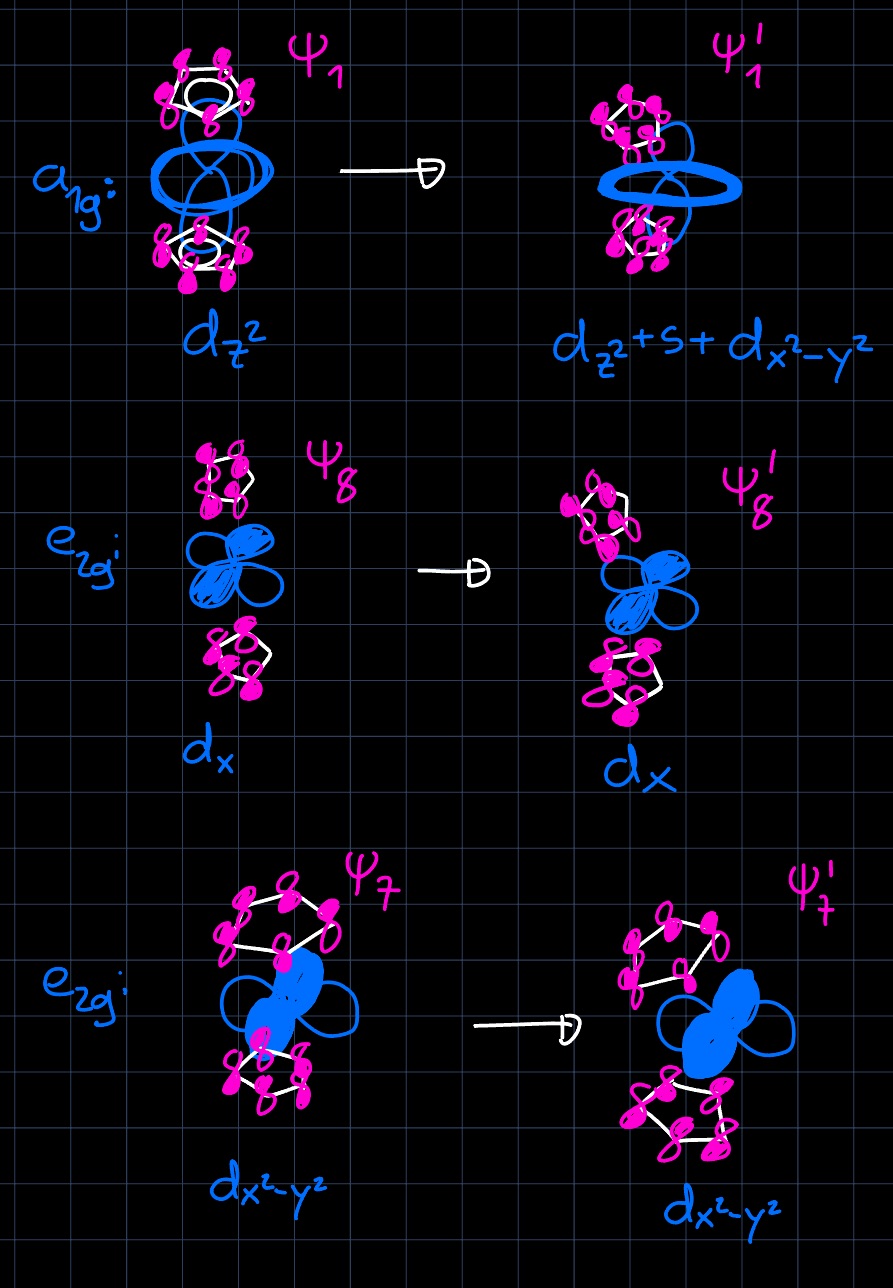

Metallocenes in linear form are (usually) not catalytically active, as they lack the low energy unoccupied d-orbitals. Bent metallocenes, however are a different story, which we again would like to understand considering the MO diagram. For this let's consider the complex $\ce{Cp2ZrCl2}$ and setup the MO diagram. As the $\ce{Cl-}$ ligands provide only occupied orbitals, we first can setup the MO diagram of $\ce{Cp2Zr^{2+}}$, where we only need to consider the empty orbitals.

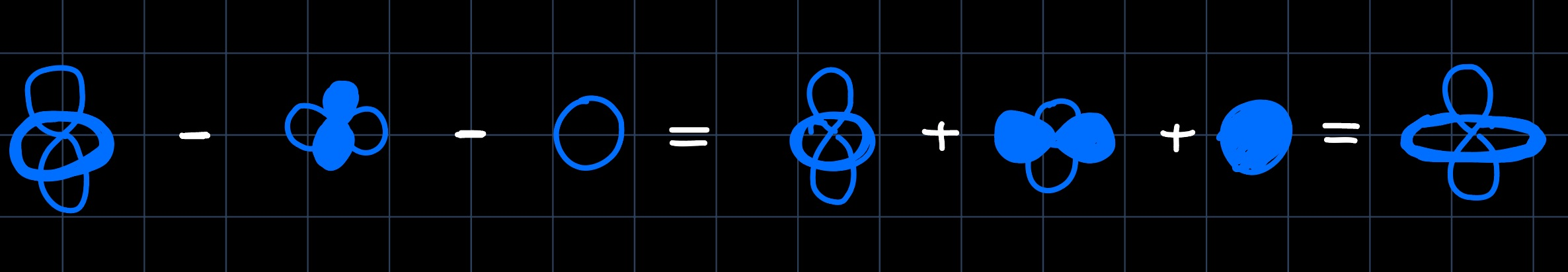

The $d_{z^2}$ orbital is of the same symmetry in the new $C_{2v}$ point group and thus mixed with the s and $d_{x^2-y^2}$ orbitals:

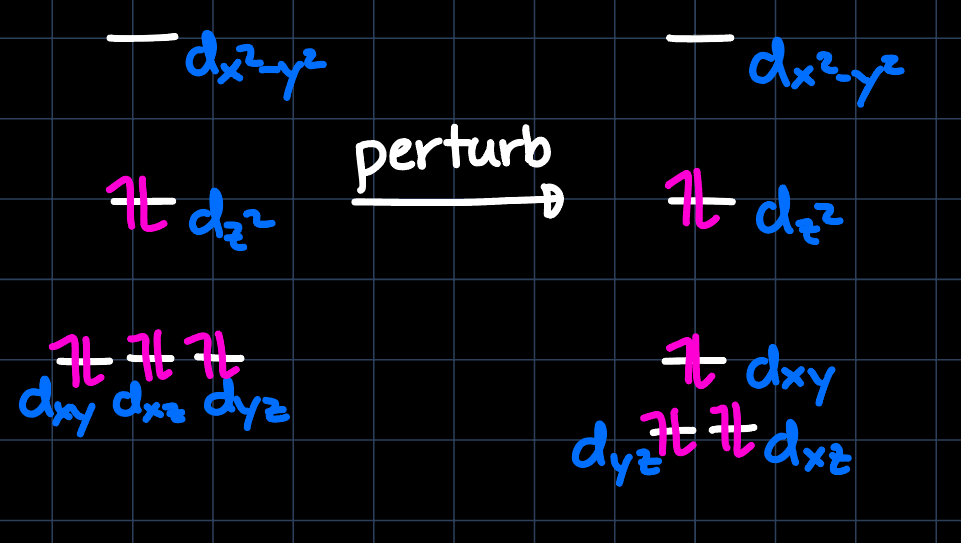

The negative coefficients of the bonding orbitals arise because it's a three orbital mixing, which can be thought of as an analogy to the allyl antibonding orbitals. Furthermore, the antibonding interactions with the $\ce{Cp2^{2-}}$ superligand with the hybrid orbital are increased and thus the hybrid orbital is increased quite a bit in energy. The $d_{xy}$ and $d_{x^2-y^2}$ are just increased in energy (a little less), as the antibonding overlap is increased. Finally we can take the previously derived MO diagram of $\ce{Cp2M}$ and perturb it by bending the ligands as:

After applying this perturbation, a new MO can be setup for the whole complex, interacting with the symmetric and antisymmetric combination of the $\ce{Cp2^{2-}}$ superligand:

Structure and Reactivity of Bent Metallocenes

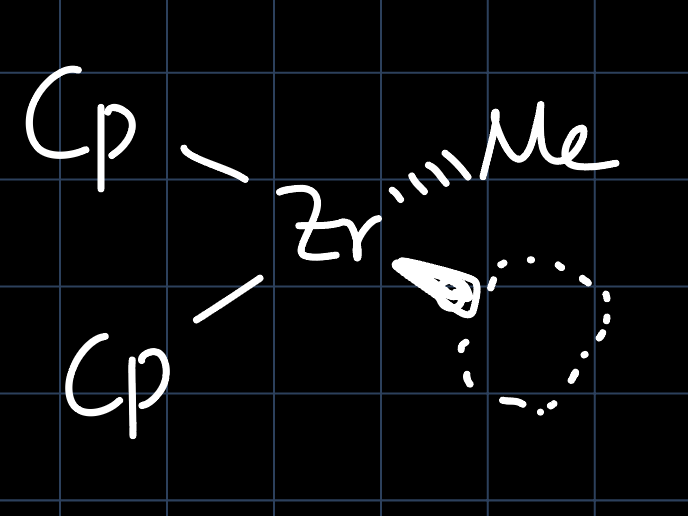

A prime example of a Ziegler-Natta catalyst for olefin polymerization is:

Considering the MO diagram for $\ce{Cp2ZrCl2}$ and removing one ligand, one can see that an unoccupied low energy d-orbital is preserved, which is a prime open coordination site for olefins:

The olefin can then undergo an insertion into the $\ce{Zr-Me}$ bond, which is the propagation step in the polymerization process.

Another observation is that for the $\ce{Cp2ZrMe}$ complex an unusually low $J_{\ce{C-H}}$ coupling constant is observed in NMR, which can be explained through the $\alpha$-agostic interaction:

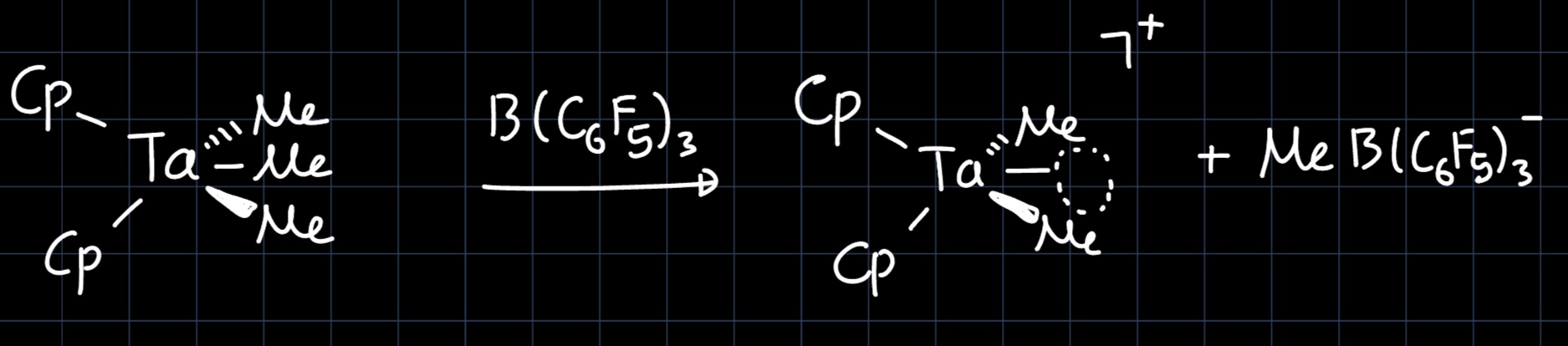

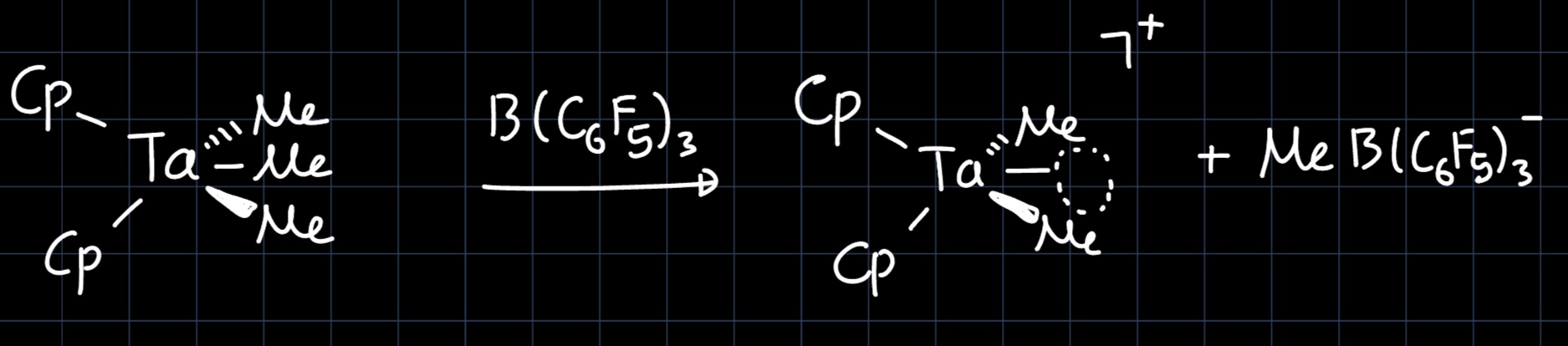

Finally we would like to examine the complex $\ce{Cp2TaMe3}$, for which all $\ce{Me}$ ligands lie in the same plane:

This makes sense, considering the MO diagram we for the bent metallocenes we have previously derived.

Furthermore, the complex is only active in olefin polymerization upon addition of a Lewis acid such as $\ce{B(C6F5)3}$, because it is fully coordinated (remember a metal has a maximum of $9$ coordination sites available, as there are $5$ d-orbitals, $1$ s-orbital and $3$ p-orbitals). The Lewis acid can abstract a $\ce{Me}$ ligand, which opens a coordination site for olefin polymerization:

Lastly, the anionic product of the reaction is observed to have very broad peaks in $\ce{^1H}$ NMR, which is explained by the reaction:

$$ \ce{MeB(C6F5)3^- <=>[+B(C6F5)3][-B(C6F5)3] B(C6F5)3-Me-B(C6F5)3^-} $$

where the $\ce{Me}$ acts as a bridge between the two $\ce{B(C6F5)3}$ ligands.

Metal Olefin Complexes

Topics Covered

- Bonding in Olefin Complexes

- Synthesis Example Olefin Complexes

- Orientation of Olefin

Bonding in Olefin Complexes

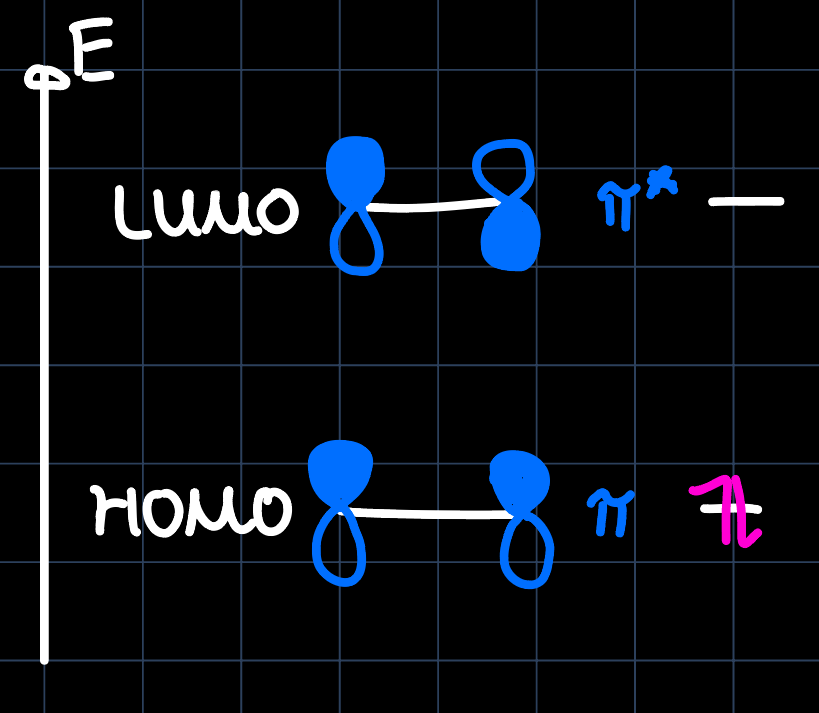

There are two bonding mechanisms to be distinguished for olefin complexes. In order to understand them, consider the MO diagram of ethylene:

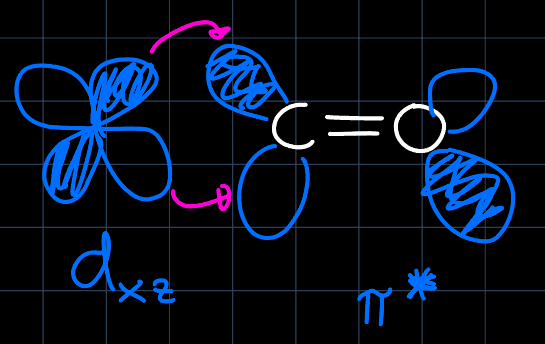

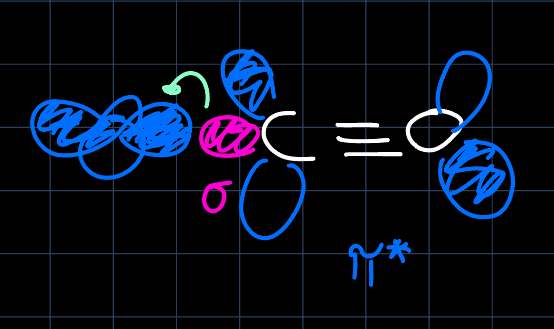

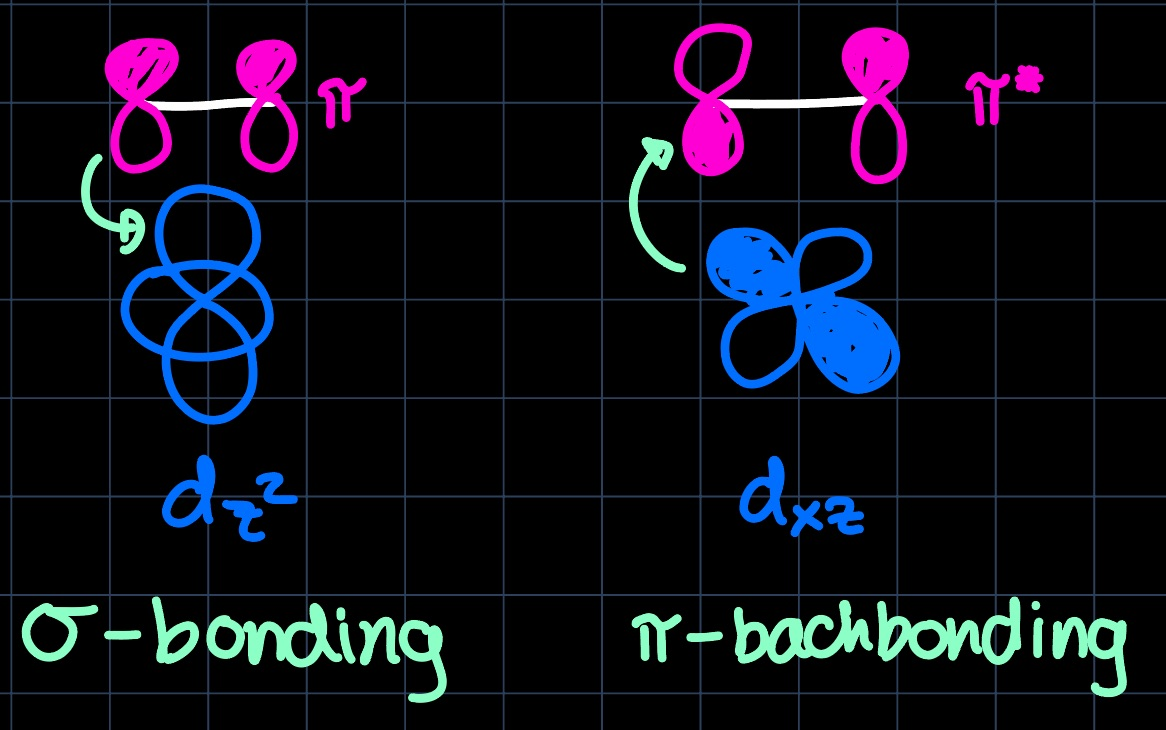

Knowing the shapes of the metals $\mathrm{d}$-orbitals, we see the overlap with the ethylene HOMO and the $\mathrm{d}_{z^2}$ orbital, forming the $\sigma$-component of the bond and the overlap of the ethylene LUMO with the $\mathrm{d}_{xz}$ orbital, forming the $\pi$-component of the bond ($\pi$-backbonding):

With the setup prepared, we can assess the situation for different transition metals (TMs), i.e. compare early and late transition metals. The difference lies mostly in the $\pi$-backbonding ability of the metal and manifests in the $\ce{C-C}$ bond length, which in case of strong backdonation is lengthened as the bond order is decreased.

For early TMs, we distinguish between $\mathrm{d}^0$ metals, which cannot do $\pi$-backbonding as there are no electrons. In contrast, early TM with a non-zero $\mathrm{d}$-electron count have a strong ability for $\pi$-backdonation, as they are rather electropositive. Late transition metals only exhibit weak $\pi$-backbonding, as they are more electronegative, since they have a higher nuclear charge and thus don't donate electrons as easily.

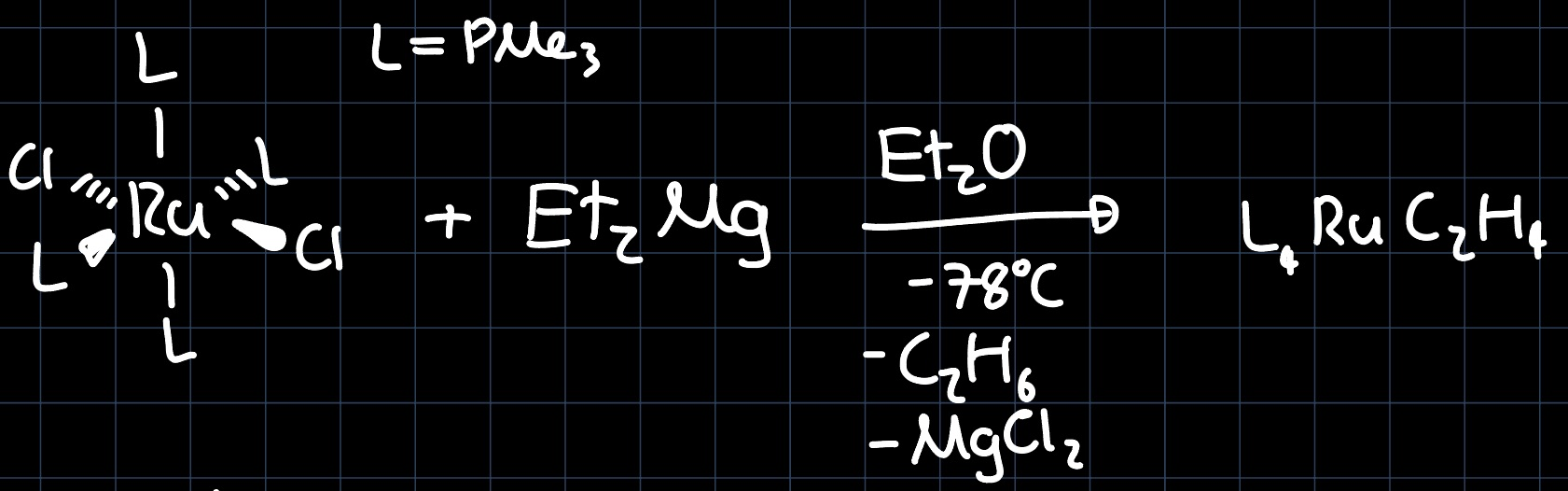

Synthesis Example Olefin Complexes

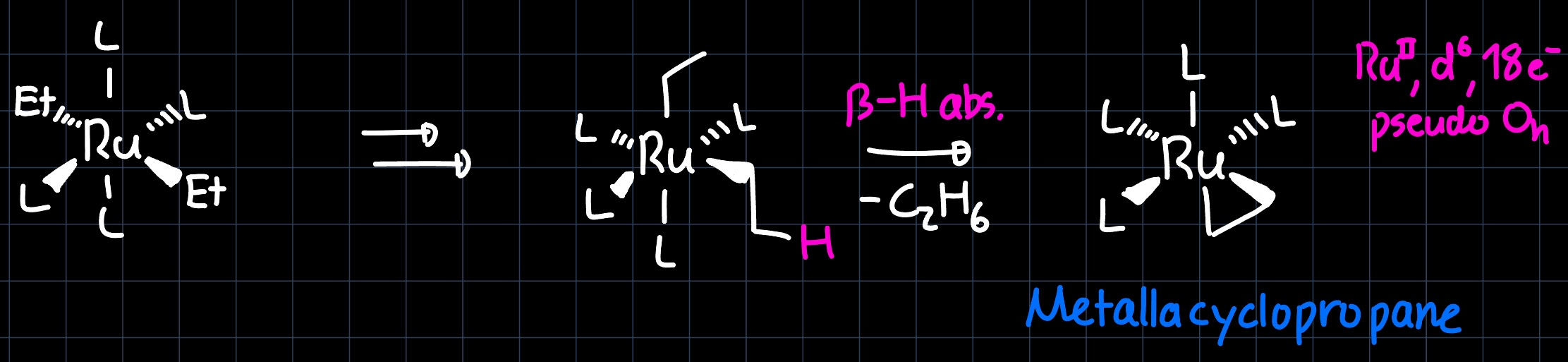

Amongst other processes, olefin complexes can be synthesized from metal alkyls by different processes. Consider the reaction:

In a first step, the $\ce{Cl}$ are substituted by the $\ce{Et}$ ligands, which then can undergo different processes to produce a metal olefin. One possibility is through an $\alpha-\ce{H}$ abstraction:

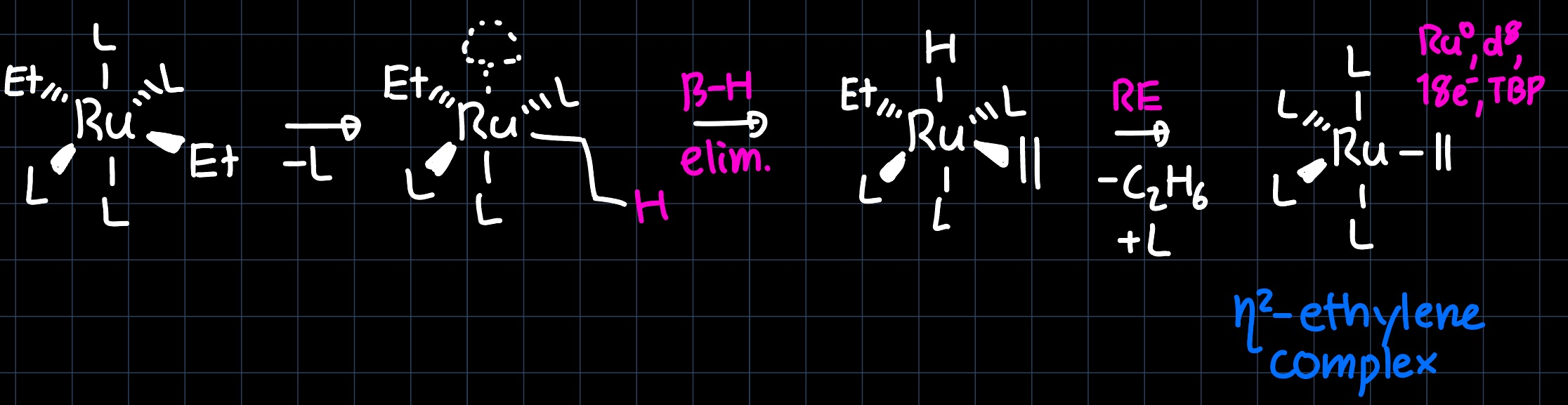

where a metallacyclopropane is formed, which is the full $\pi$-backdonation bonding scenario of the metal olefin bond. Another possibility is that the metal alkyl undergoes a $\beta-\ce{H}$ elimination step with a subsequent reductive elimination:

which produces the same product, but now in the form of only $\sigma$-bonding and no $\pi$-backdonation. As usual, the reality lies somewhere between the two extremes, with a slight preference for the $\pi$-backdonation scenario.

Conducting the same reaction at room temperature yields the product $\ce{[Ru(PPh3)4(H)(Et)]}$, with the two X-type ligands in cis-geometry. The reaction proceeds through a similar mechanism as before, but now the ethylene ligand is substituted before the reductive elimination happens, leading to a different product:

Orientation of Olefin

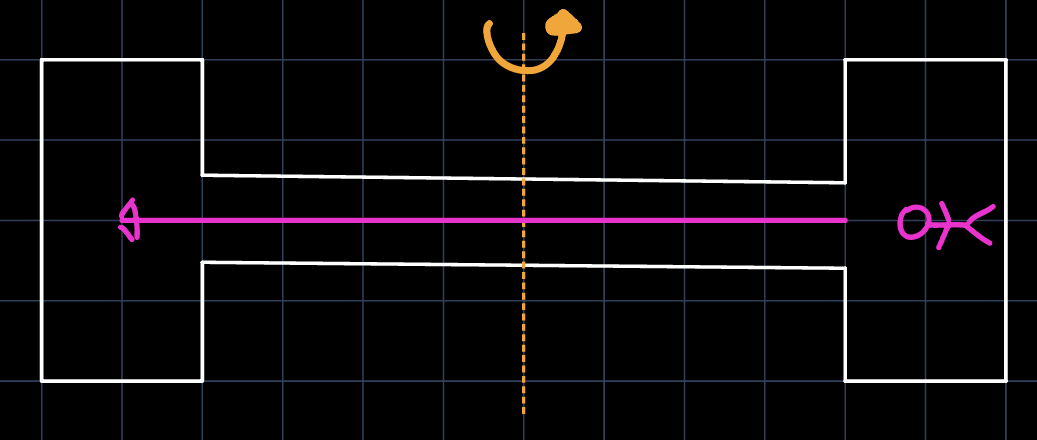

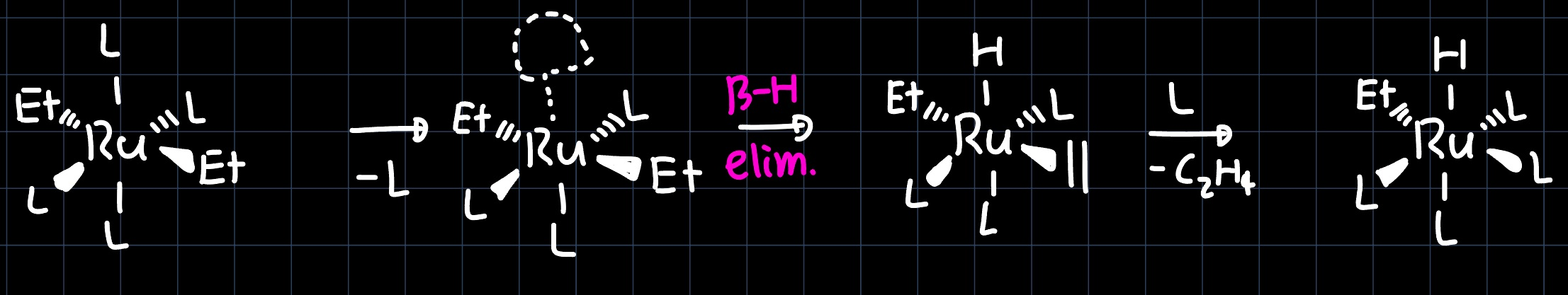

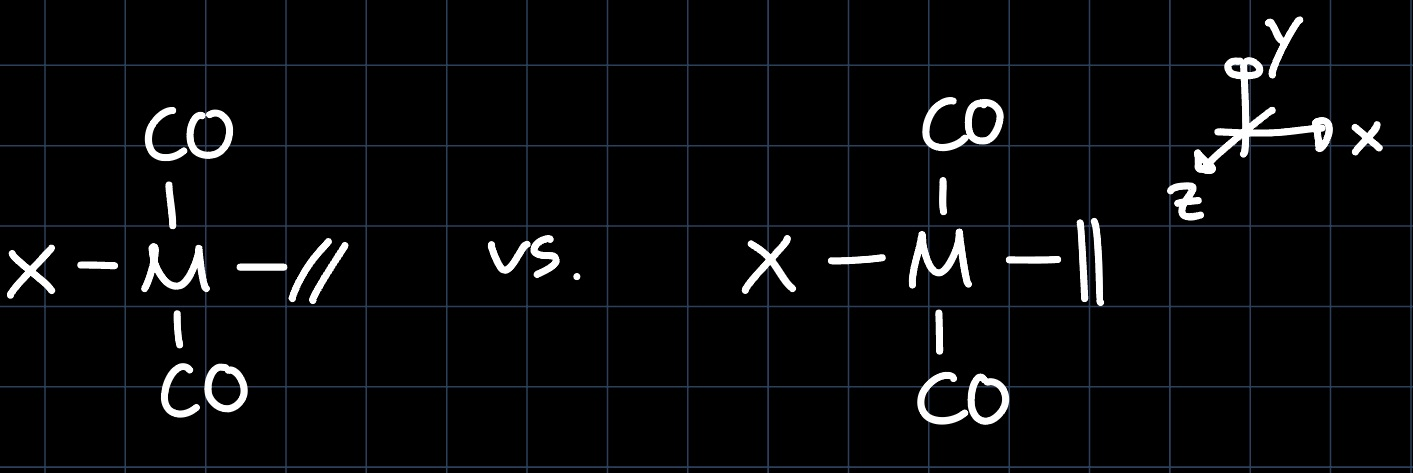

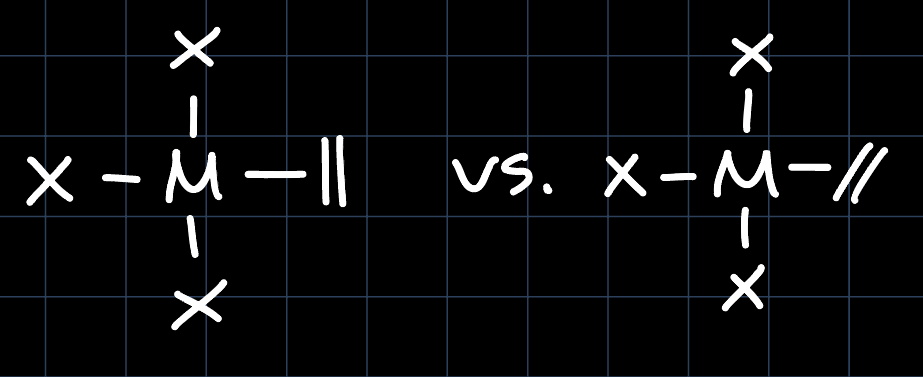

The orientation of the olefin in a metal complex is mainly governed by electronic effects, which can be rationalized from the MO diagram of the structure. As the $\sigma$-bonding remains unchanged upon rotation, the $\pi$-bonding is affected by the orientation of the olefin. So the stability only depends on the strength of the $\pi$-interaction between the metal $\mathrm{d}$-orbitals and the $\pi^{\ast}$-orbital of the olefin. Let's discuss this with a few examples: Assume $\ce{X}$ to be a pure $\sigma$-donor (no $\pi$-effects) and a $\mathrm{d}^8$ metal.

Example 1: Trigonal Bipyramidal

Considering the MO diagram of the trigonal bipyramidal structure:

we see that the $\mathrm{d}_{xy}$ orbital is higher in energy than the $\mathrm{d}_{xz}$ and $\mathrm{d}_{yz}$ orbitals. Thus, the $\pi$-backbonding is stronger in the equatorial plane than in the axial position. This leads to a preference for the olefin to be in the equatorial plane (left side in the drawing).

Example 2: Square Pyramidal with CO

Similarly as for the trigonal bipyramidal structure, we consider the MO diagram of the square pyramidal geometry, which however due to the $\ce{CO}$ ligands needs to be slightly perturbed:

The best interaction is thus given by the $\mathrm{d}_{xy}$ orbital, which makes the structure drawn on the left favorable. This also makes sense intuitively: In the structure on the right, the strong $\pi$-acceptor $\ce{CO}$ ligands would be competing with the olefin for the $\pi$-backbonding interaction and thus offer less stability.

Example 3: Square Planar with CO

Again, we take the MO diagram of the square planar geometry and slightly perturb it due to the $\ce{CO}$ ligands:

Just as before, the $\mathrm{d}_{xy}$ orbital is higher in energy than the $\mathrm{d}_{xz}$ and $\mathrm{d}_{yz}$ orbitals and thus the best interaction partner for the olefin, leading to the structure on the left being the most stable.

Example 4: Square Planar without CO

In the absence of $\ce{CO}$ ligands, the $\mathrm{d}_{xy}, \mathrm{d}_{xz}$ and $\mathrm{d}_{yz}$ orbitals are degenerate and thus we don't find an electronic effect that would favor one orientation over the other. In this case we would have to consider steric effects, mostly originating from the cis-ligands, but this is highly dependent on the specific ligands.

Telomerization, Carbenes and Hydrocyanation

Topics Covered

- Telomerization

- Fischer Carbenes vs. Schrock Alkylidenes

- NHCs and CAACs

- Hydrocyanation

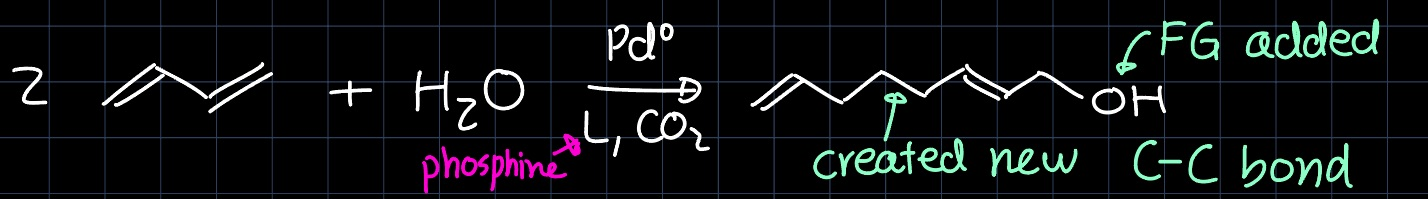

Telomerization

In the lecture we have covered another aspect of the beauty in the chemistry of dienes, namely the telomerization reaction:

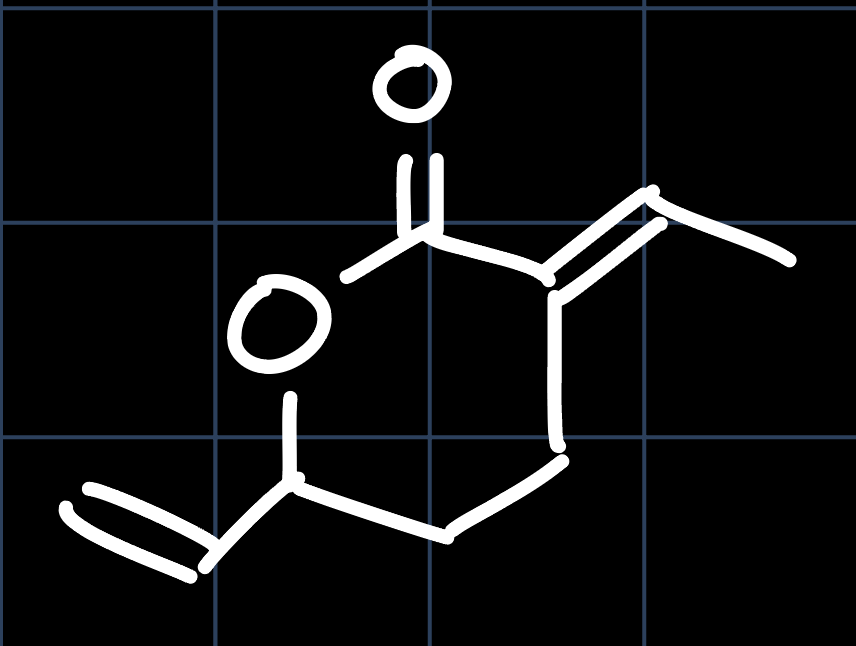

However, this is only one example in a wide variety of products that can be obtained through the telomerization reaction of butadiene. Also from two equivalents of butadiene and one equivalent of $\ce{CO2}$ in the presence of a Palladium catalyst, the following lactone is obtained:

The catalytic cycle that leads to this lactone is similar to what we have seen in the lecture, but as no water is present, there is no formation of $\ce{HCO3-}$, and $\ce{CO2}$ will insert into the $\ce{Pd-C}$ bond:

.png)

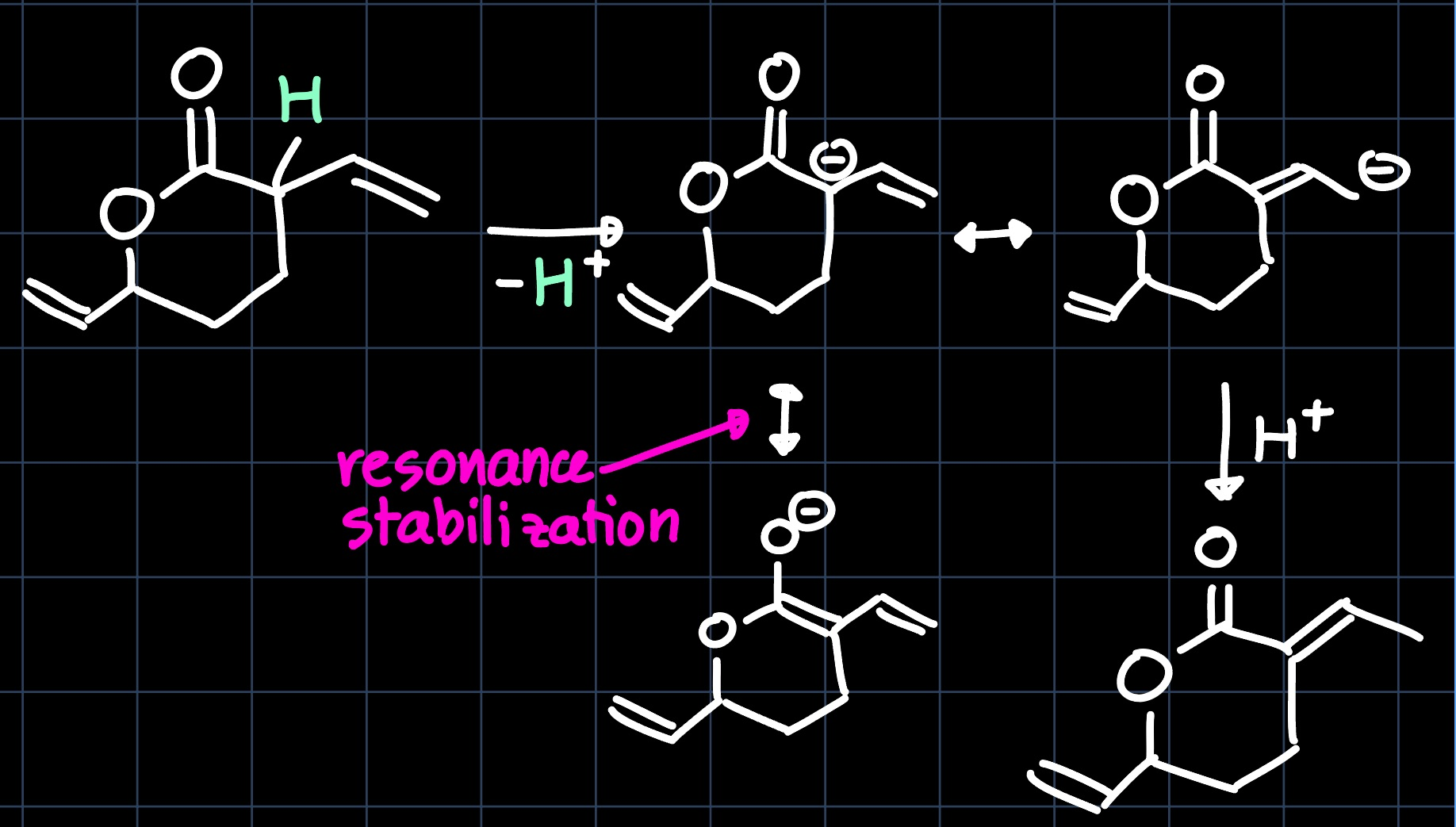

However, there is still a small difference between the obtained product and the one yielded by the catalytic cycle. This is because it will undergo a tautomerization reaction, as the $\ce{H}$ in $\beta$ position to the $\ce{C=O}$ group is slightly acidic:

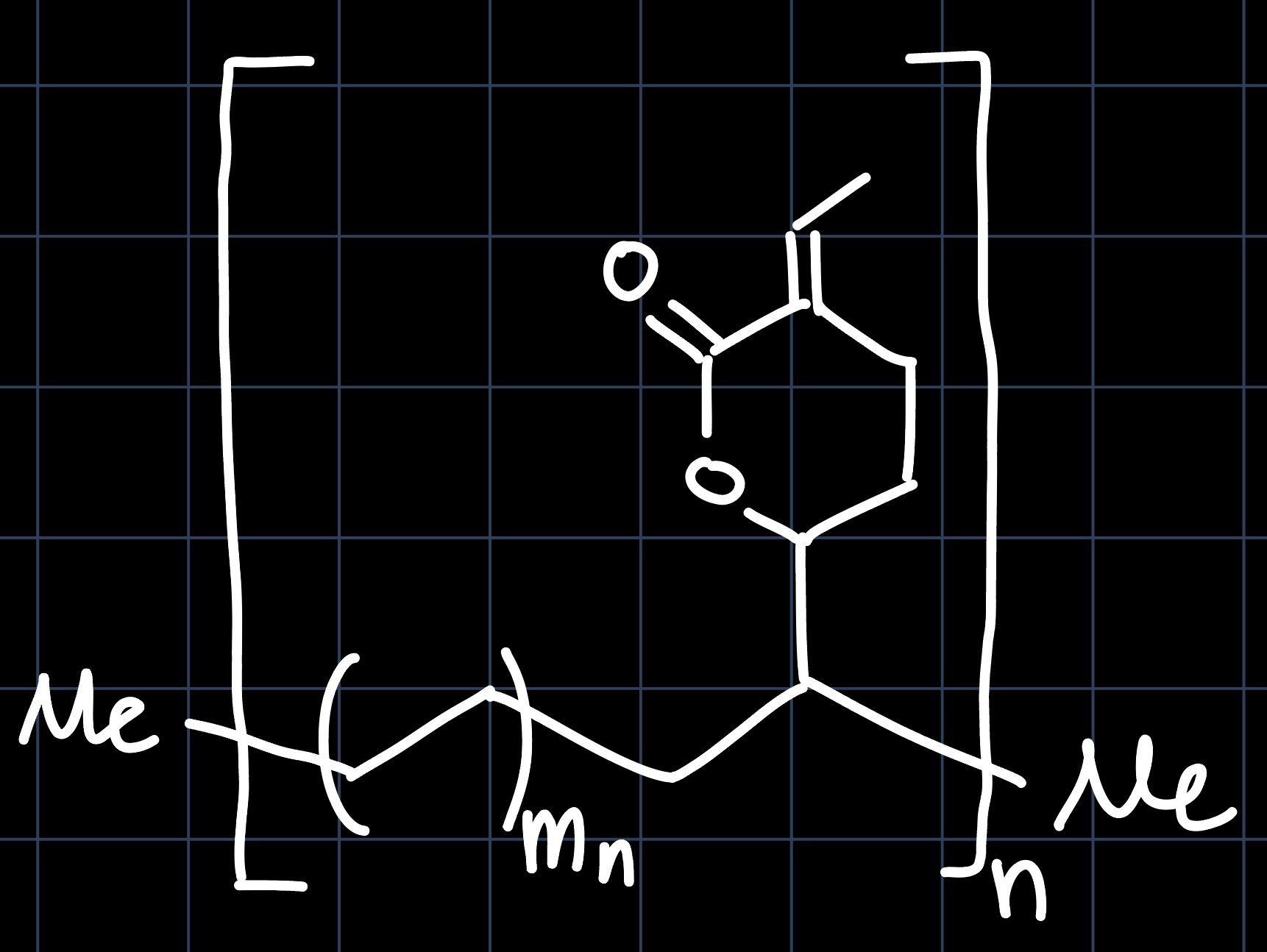

Palladium catalyzed co-polymerization of the discussed lactone with ethylene yields an interesting polymer:

The reaction mechanism yielding this polymer is similar to a simple polymerization of ethylene, but the co-polymerization introduces some complexity:

The polymer chain lengths $n, m_n$ depend on the catalyst employed and the reaction conditions. Of course, in practice a variety of products is obtained. Nevertheless, we do observe a selectivity for the terminal double bond of the lactone, as it is favored by both sterics (better accessibility) and electronics (not $\alpha$ to carbonyl, so less electron deficient).

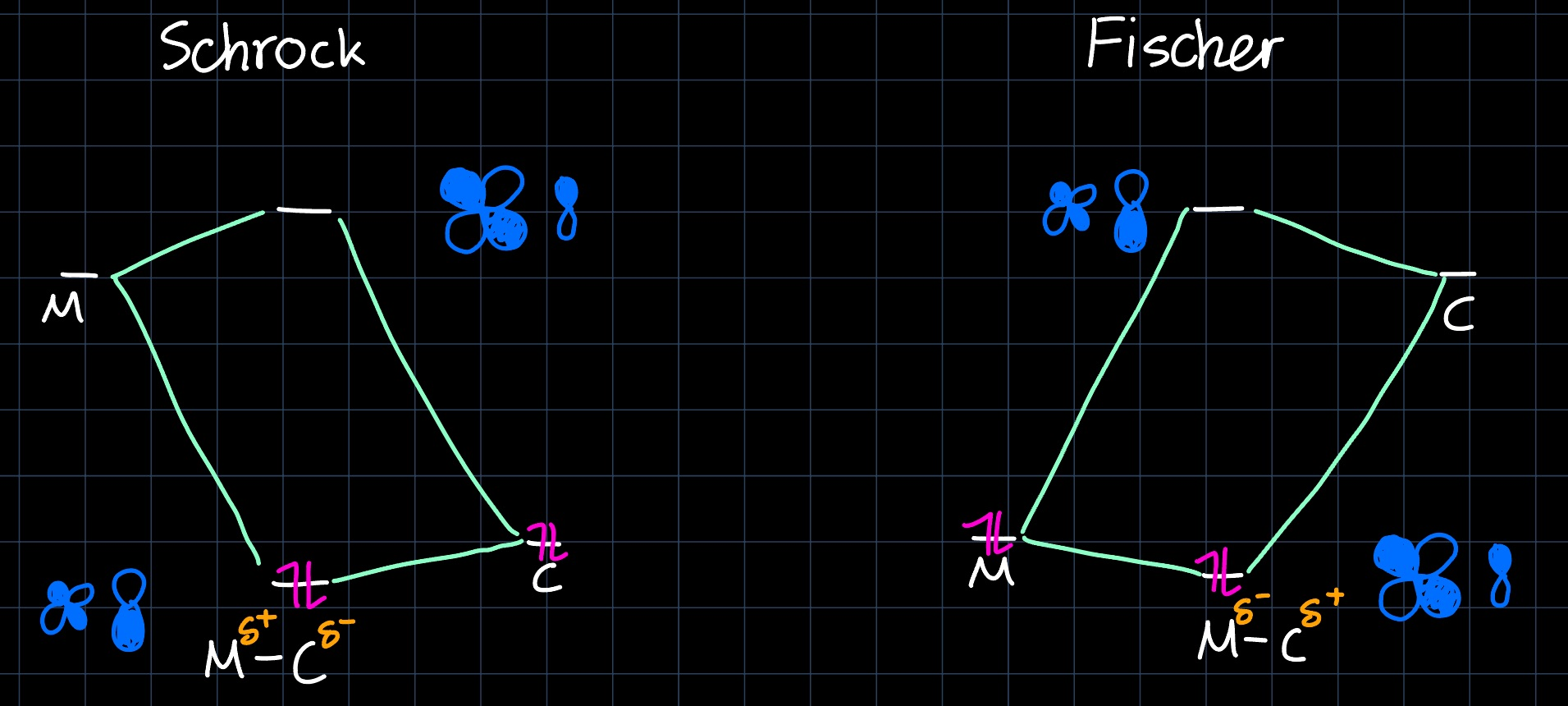

Fischer Carbenes vs. Schrock Alkylidenes

Although they share the same lewis structure, Fischer Carbenes (usually $d^6$ metals like $\ce{Cr^0}$, $\ce{Mo^0}$, $\ce{Fe^{II}}$, ...) and Schrock Alkylidenes (usually $d^0$ metals like $\ce{Mo^{VI}}$, $\ce{W^{VI}}$, $\ce{V^{V}}$, ...) behave chemically very different. They both act as $\sigma$ donors and $\pi$ acceptors:

However, due to the difference in energy levels, the electrons are ligand based in Schrock Alkylidenes, while they are metal based for Fischer Carbenes, resulting in a different polarity:

This results in Fischer Carbenes reacting as electrophiles and Schrock Alkylidenes reacting as nucleophiles.

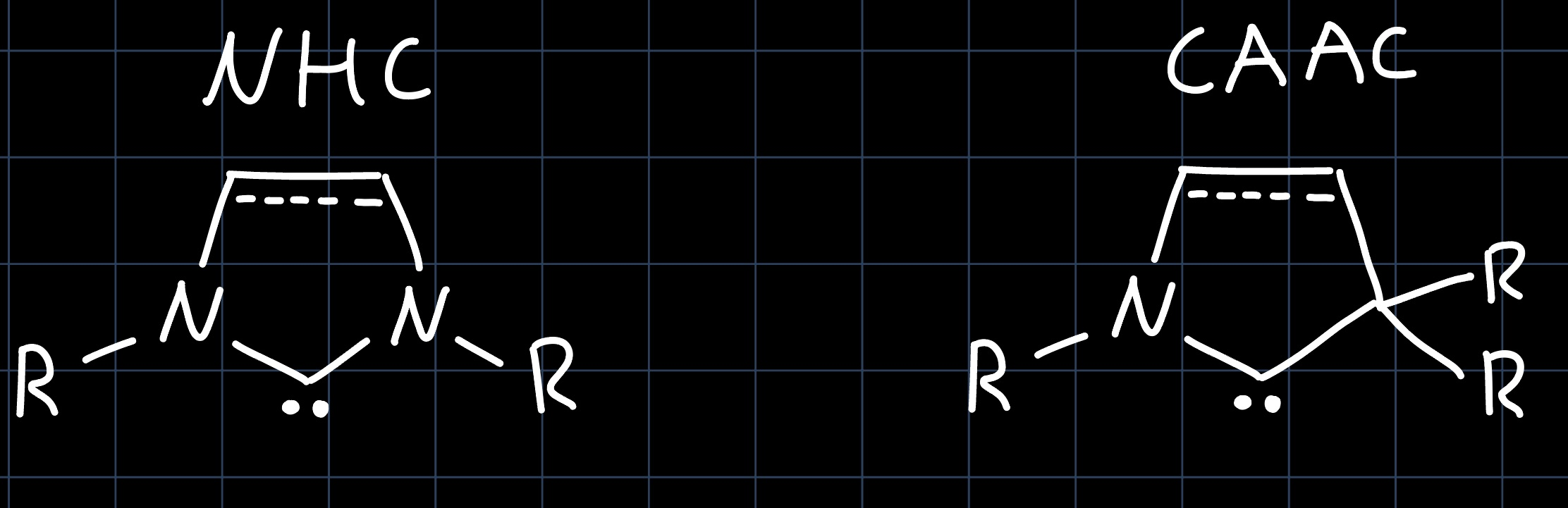

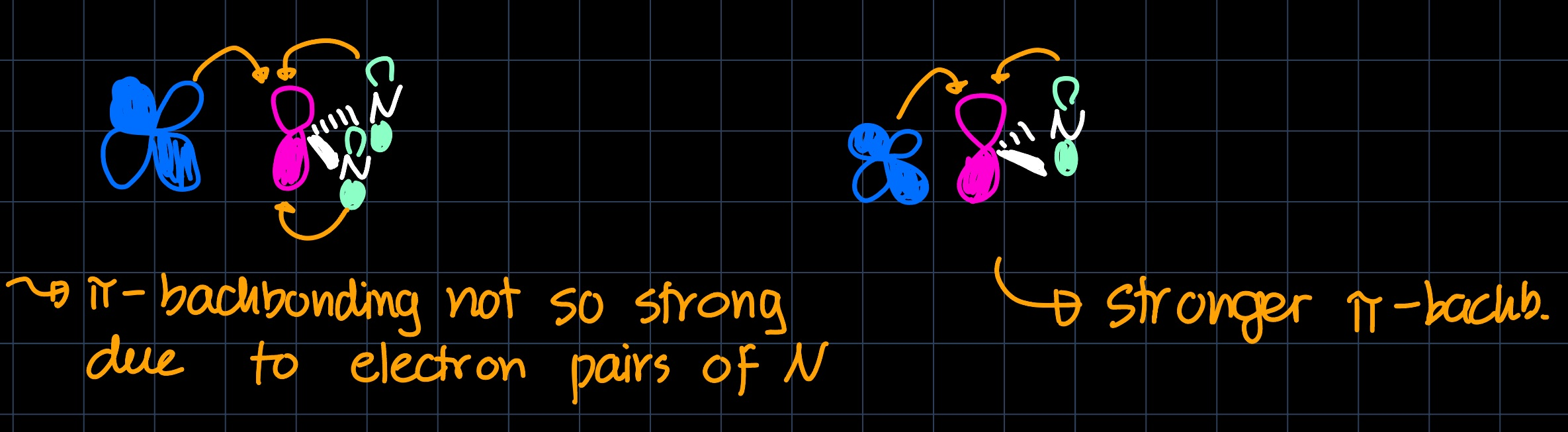

NHCs and CAACs

N-Heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs) and cyclic alkyl amino carbenes (CAACs) are two important classes of carbenes that can be used in catalyst design:

They are both strong $\sigma$ donors, however the $\pi$-acceptor ability differs, with NHCs being weaker $\pi$-acceptors than CAACs. This arises from electron donation from the lone pairs of the nitrogen atoms into the empty carbon $p$-orbital:

This difference in $\pi$-acceptor ability can be used to tune the reactivity of the catalyst and thus the selectivity towards different products.

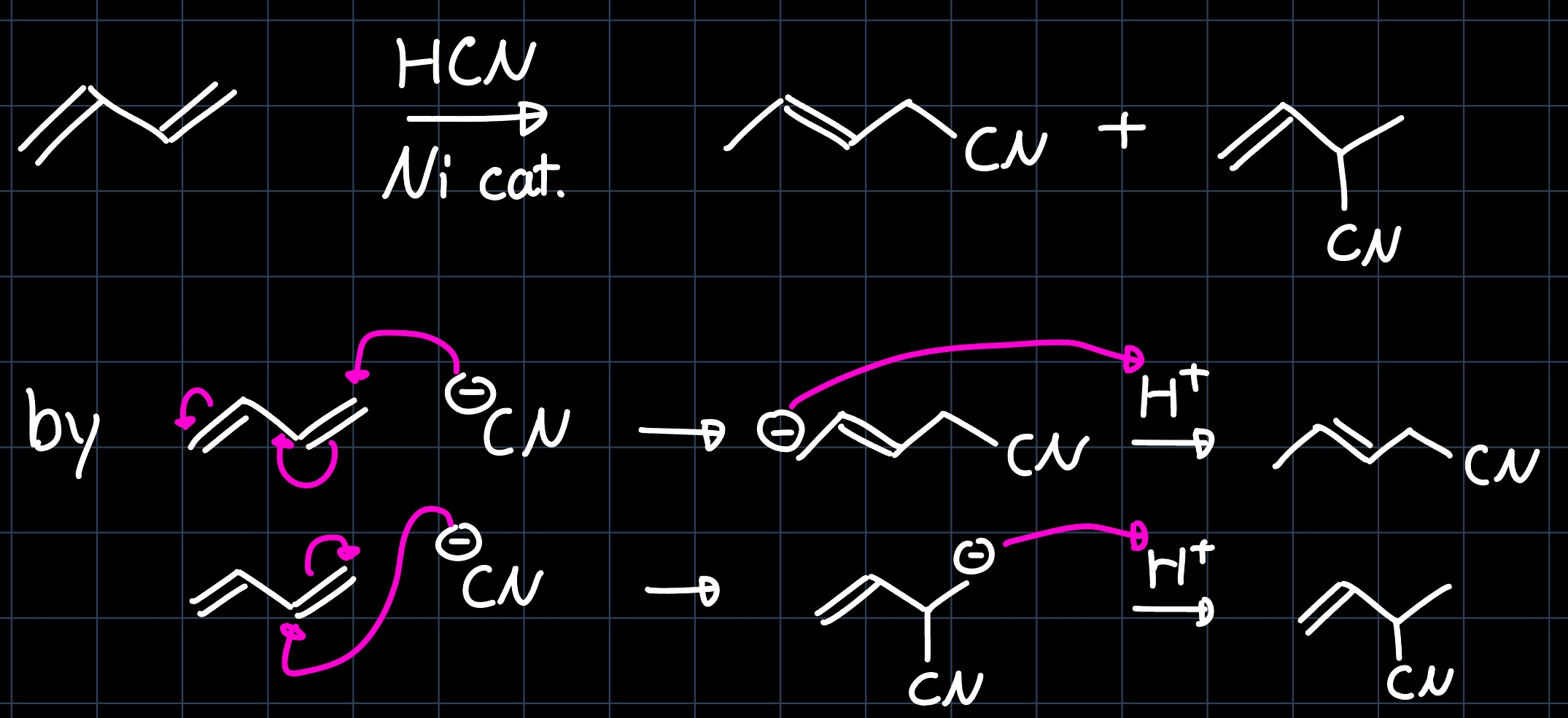

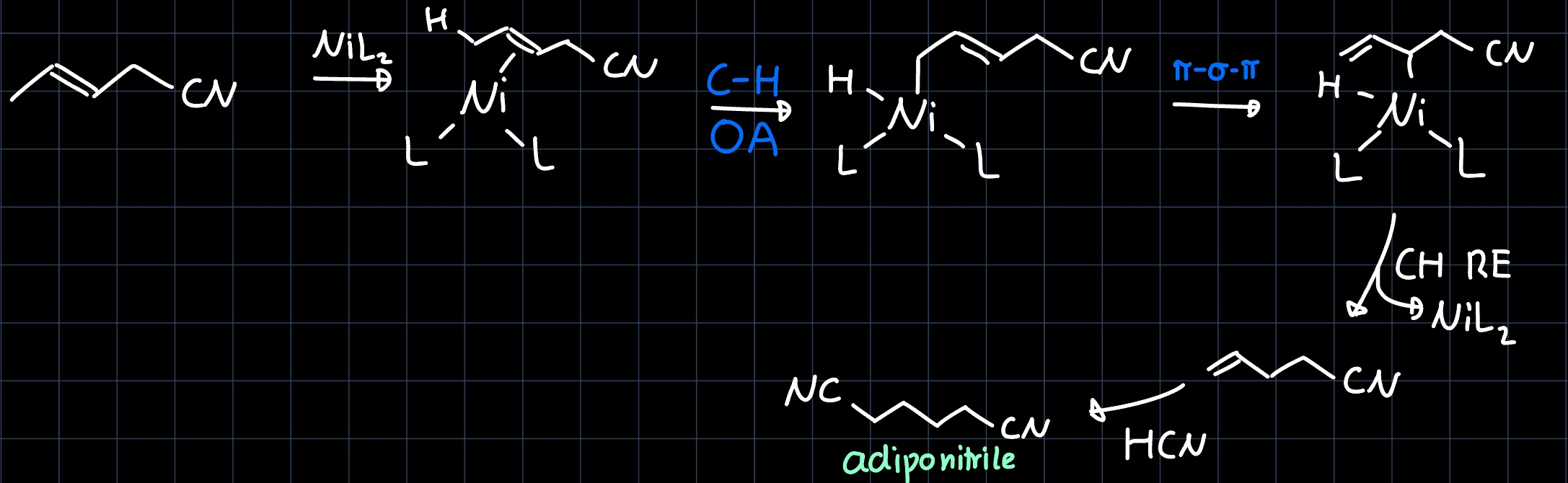

Hydrocyanation

The hydrocyanation of butadiene to adiponitrile ($\ce{NC-CH2-CH2-CH2-CH2-CN}$) is carried out industrially on a multi ton scale, as adiponitrile is a precursor for the production of nylon. The reaction proceeds via two steps. In the hydrocyanation of the first double bond, two products are be obtained in a similar ratio:

However, only one of them reacts further in the second step, yielding adiponitrile:

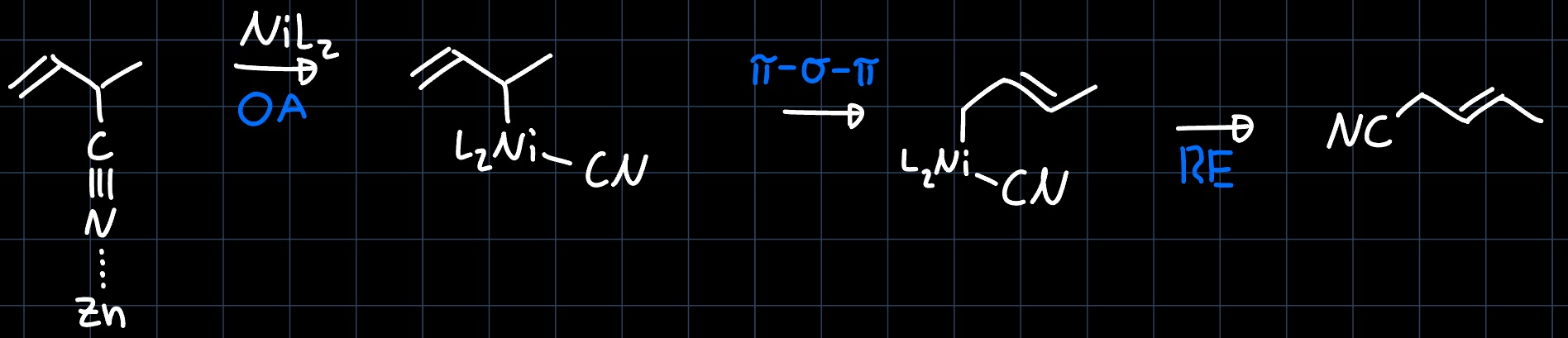

Because industry doesn't like yields of less then $50 \%$, catalytic amounts of lewis acid such as $\ce{Zn^{2+}}$ are added in order to polarize the $\ce{C-CN}$ and thus facilitate the oxidative addition to the $\ce{Ni}$ catalyst:

CH-Functionalization & Olefin Metathesis

Topics Covered

- Iridium Pincer Complex for Alkane Functionalization

- Tebbe's Reagent

- Alkyne Metathesis

Iridium Pincer Complex

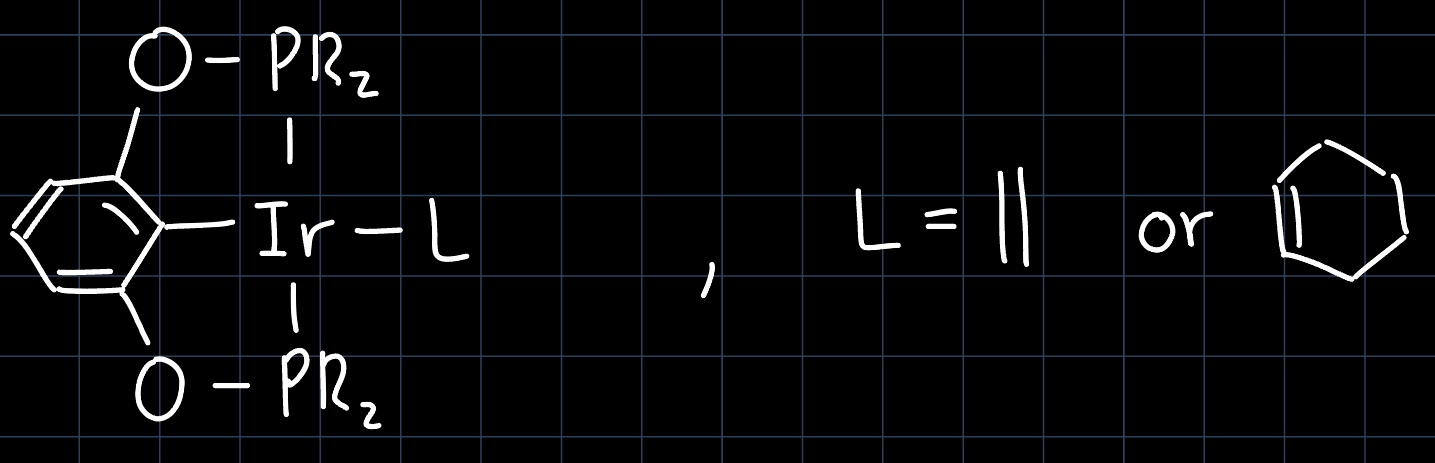

In the lecture we have considered the Shilov-Cycle as an example for CH-functionalization, where the goal was to produce methanol ($\ce{CH3OH}$) from methane ($\ce{CH4}$). Unfortunately the reaction is still not employed in industry, as methanol simply is not valuable enough to invest the energy required to separate it from the sulfuric acid that also appears in high concentrations. However, the concept of CH-functionalization remains important, as there are reactions that produce more valuable than just methanol. For example the Iridium Pincer Complex:

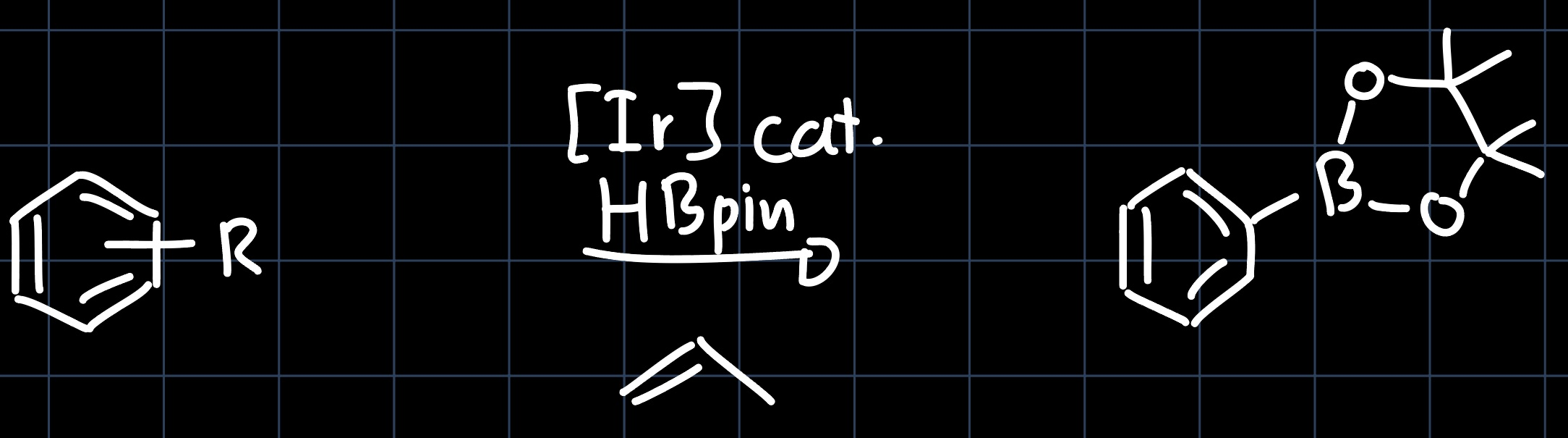

can be used for borylation of aromatic systems, producing precursors for the Suzuki coupling:

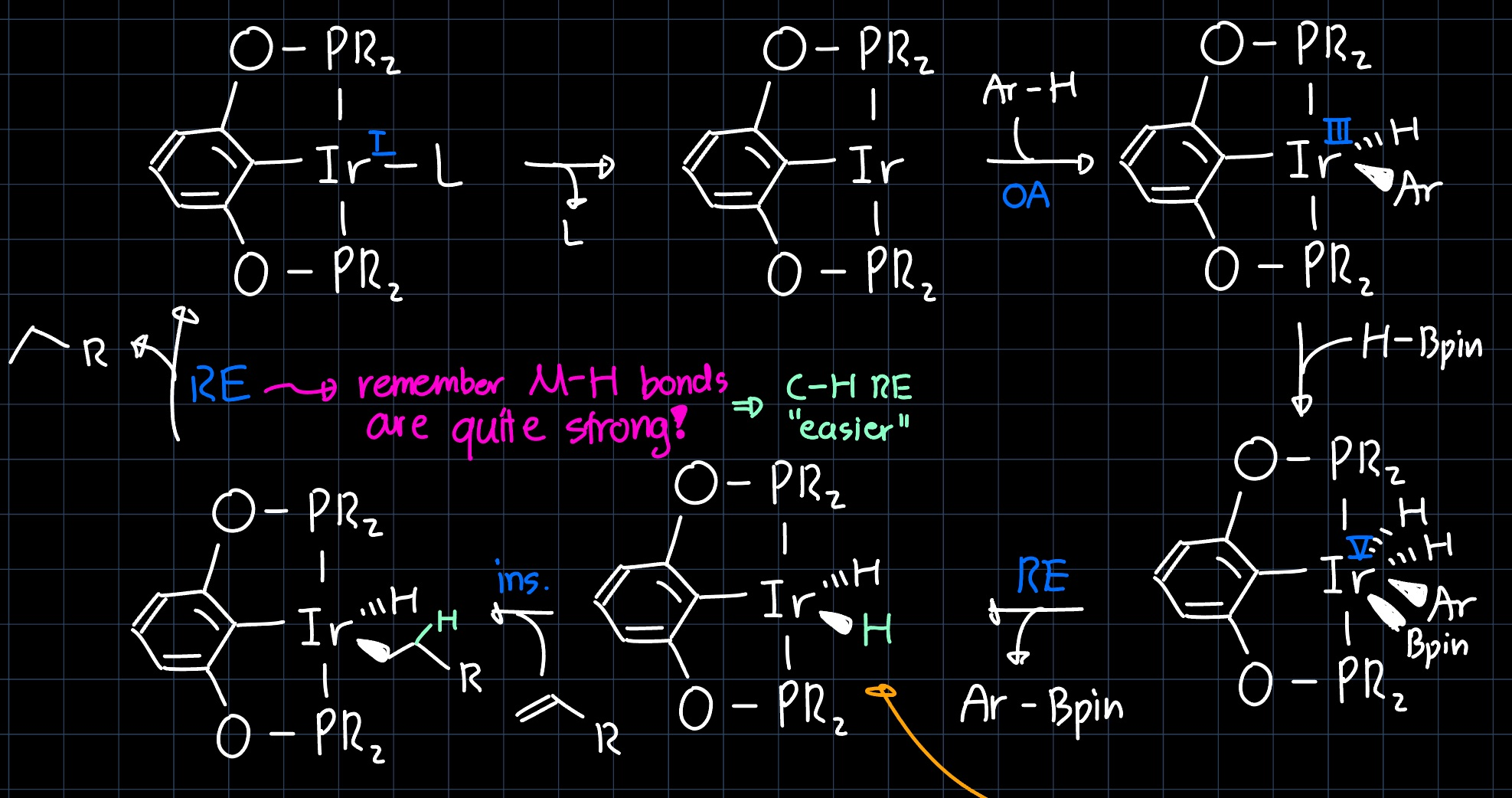

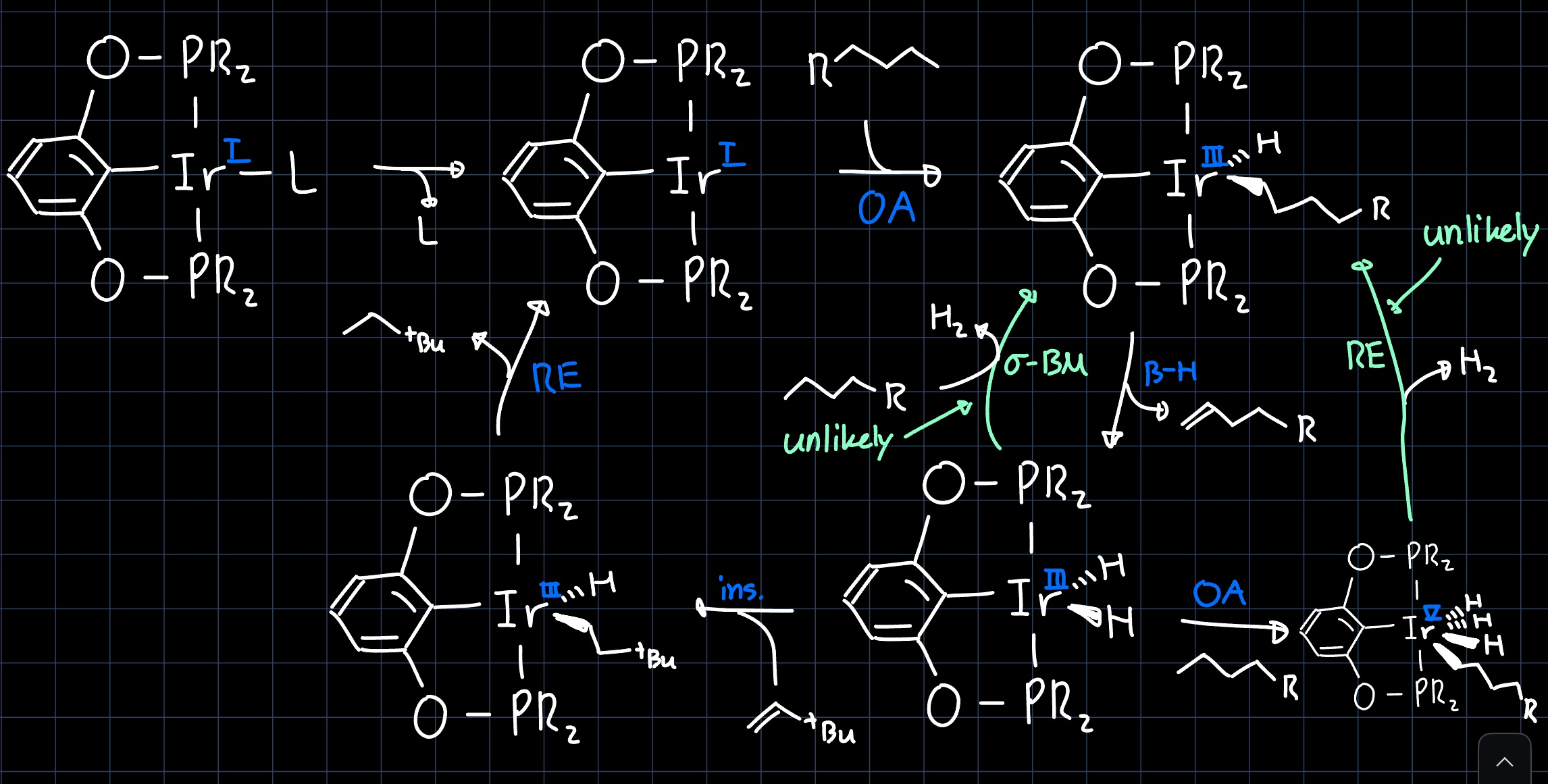

The reaction proceeds over a mechanism where iridium appears in many oxidation states ($\ce{Ir^{I}}$, $\ce{Ir^{III}}$, $\ce{Ir^{V}}$), which is why the specific structure of the Pincer Complex is important for the reaction to proceed. The suggested mechanism is shown below:

The terminal olefin $\ce{R-=}$ that is added in stoichiometric amounts serves as an $\ce{H2}$-acceptor, so it is reduced to the corresponding alkane. it is required since the middle intermediate in the lower row does not eliminate $\ce{H2}$ even if left for $24 \, \mathrm{h}$ under vacuum (at room temperature). This can be reasoned by the fact that the $\ce{Ir-H}$ bond is thermodynamically quite stable, so a reductive elimination doesn't occur where two of these bonds would be broken.

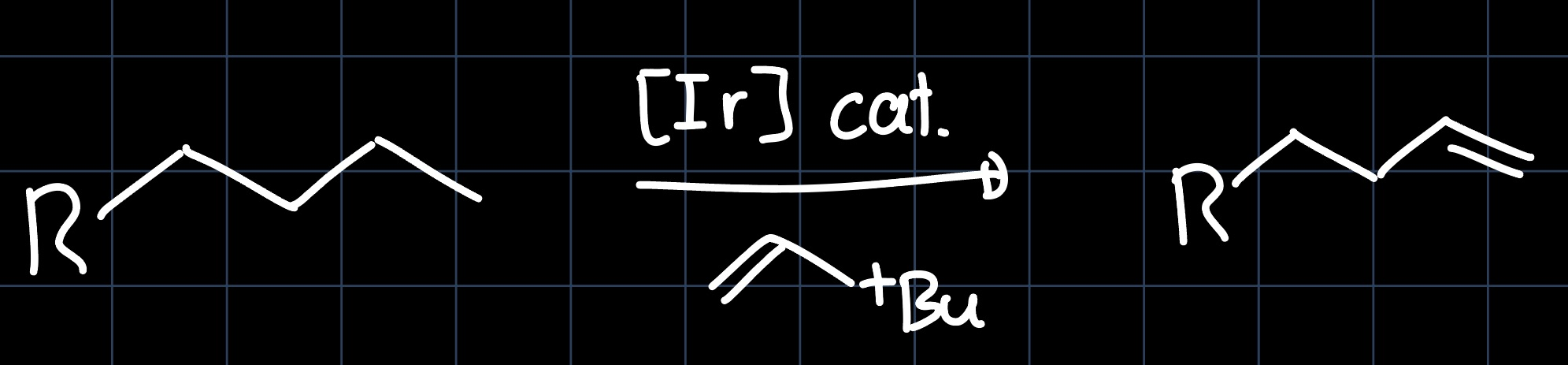

Another application of the Iridium Pincer Complex is the dehydrogenation of alkanes, where the terminal $\ce{C-C}$ single bond is converted into a $\ce{C=C}$ double bond:

The reaction can proceed over many different pathways, which are all summarized in the following scheme:

Again an alkene is needed in stoichiometric amounts to serve as an $\ce{H2}$-acceptor, as the two pathways where $\ce{H2}$ eliminates as a molecule are unlikely to occur.

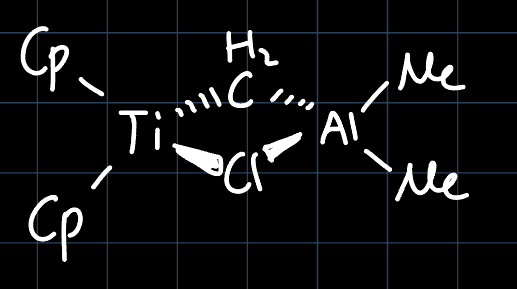

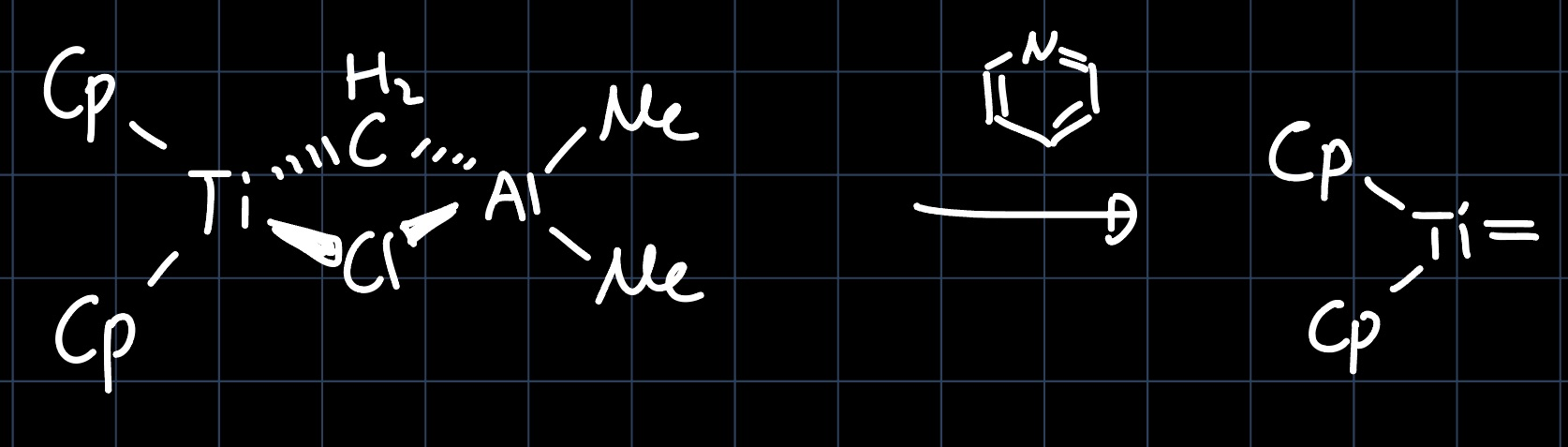

Tebbe's Reagent

The Tebbe's Reagent is a methylene transfer reagent, which is able to transform $\ce{C=O}$ double bonds into $\ce{C=C}$ double bonds. In it's inactive form (the one that is commercially available), it has the structure:

The reagent is activated by the addition of a lewis base such as pyridine:

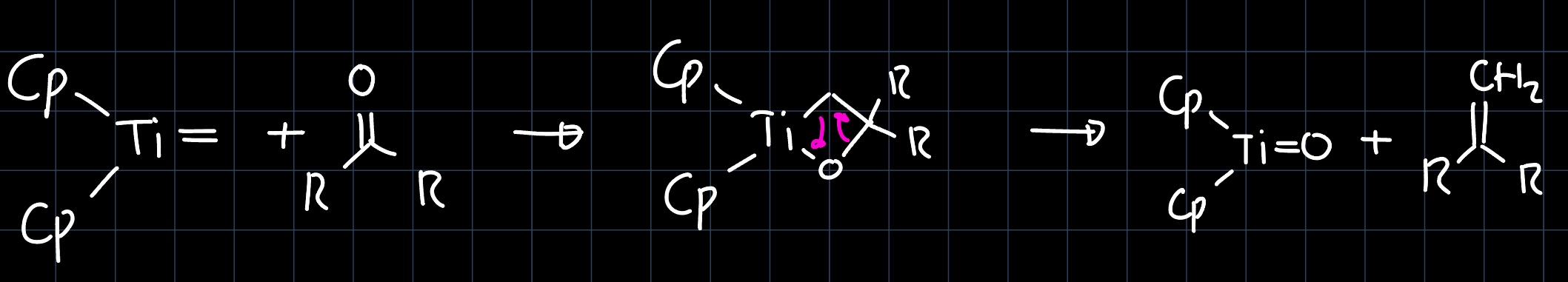

The mechanism of the methylene transfer is then analogous to the olefin metathesis mechanism:

Note that this needs stoichiometric amounts of the reagent! An example of a reaction where Tebbe's reagent can be used as a catalyst would be the ring opening metathesis polymerization (ROMP):

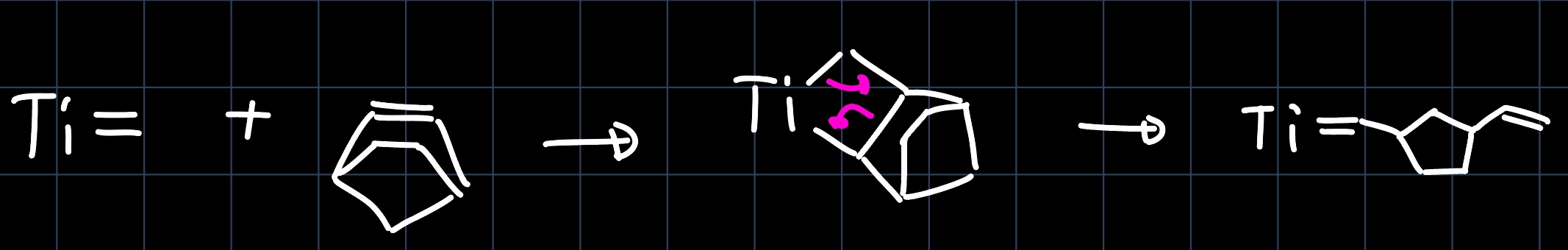

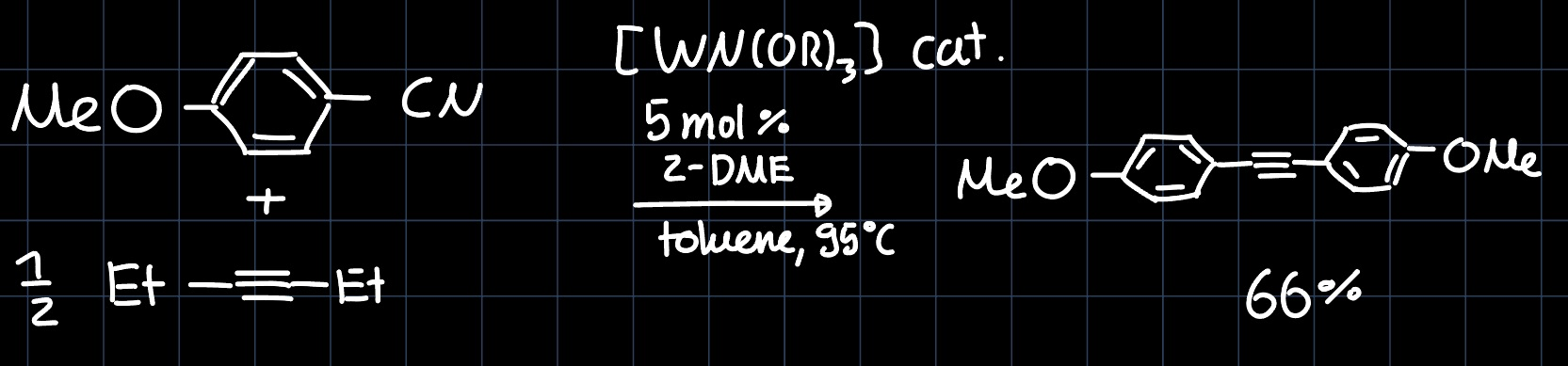

Alkyne Metathesis

Another reaction similar to olefin metathesis is the alkyne metathesis, where the substituents of a triple bond are exchanged. Consider the reaction:

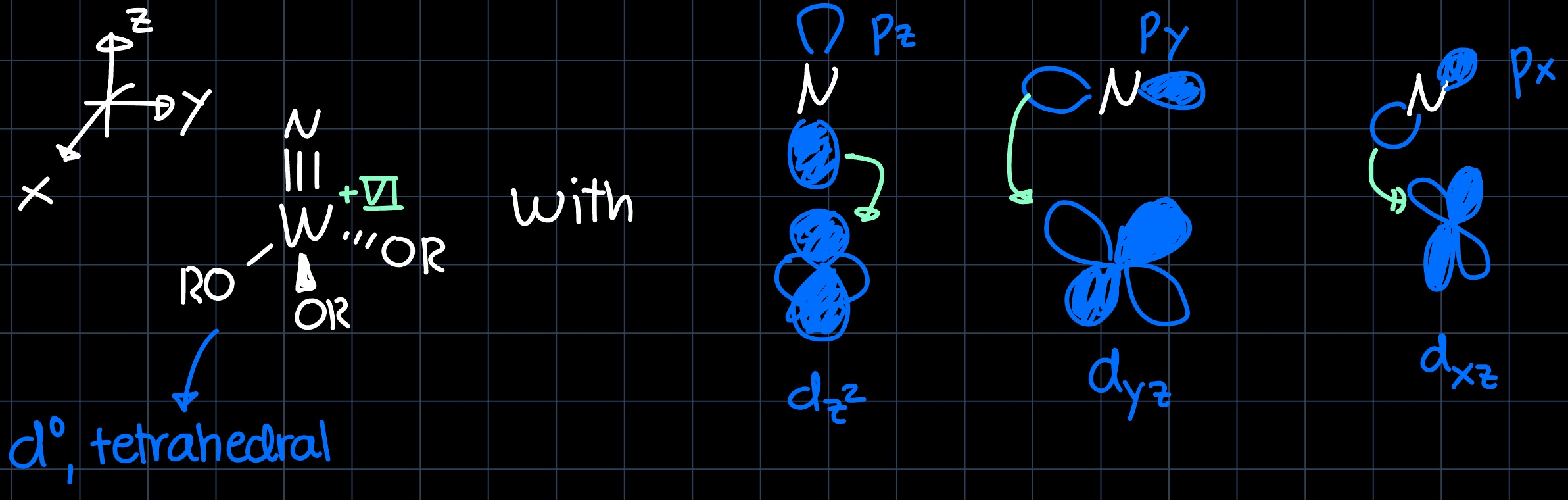

Firstly we would like to understand the structure of the catalyst, which contains a $\ce{W#N}$ triple bond. It is formed by interaction of the $p$ orbitals of the nitrogen with the $d$-orbitals of tungsten:

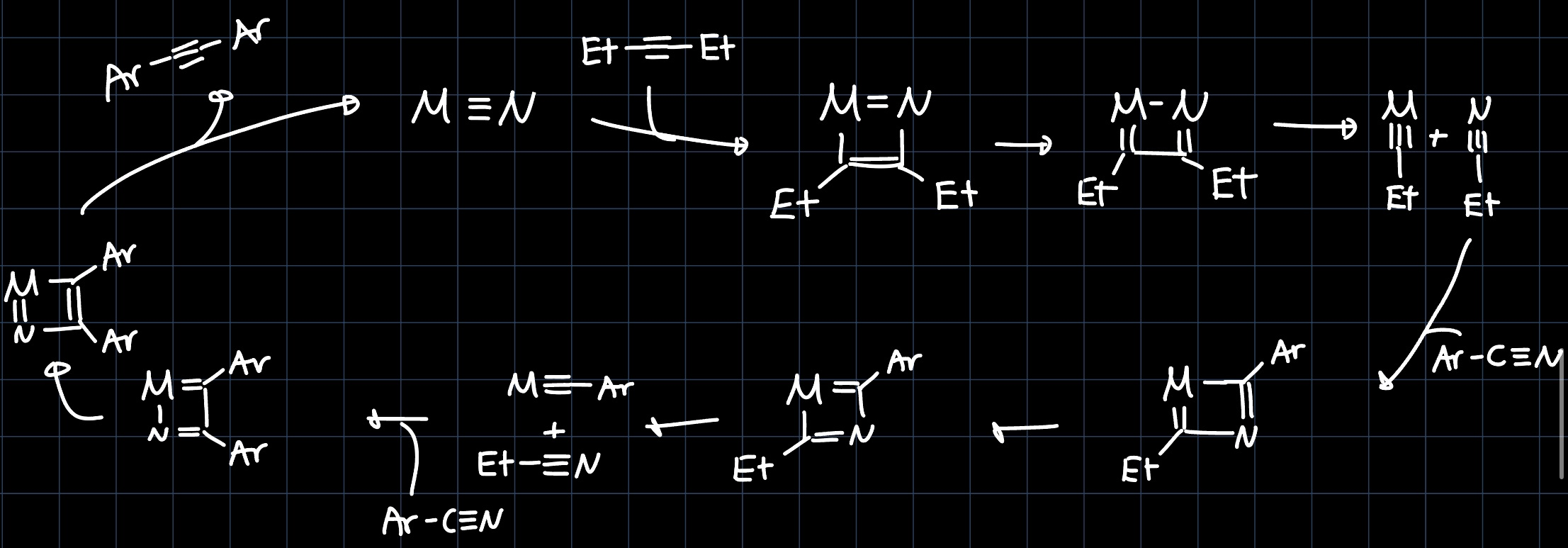

The reaction mechanism can be elucidated by thinking about always keeping in mind that the steps should be product leading and one gets:

Hydrogenation and Hydrocyanation

Topics Covered

- Hydrogenation of Alkenes

- Dihydrogen Complexes

- Selective Hydrocyanation of Arenes

Hydrogenation of Alkenes

Earlier in the lecture we have investigated the properties and synthesis of hydride complexes. Now we want to dive a bit deeper into the reactivity of such complexes by considering the hydrogenation of alkenes. The order of reactivity can be summarized as follows:

Based on this series we can predict the major product of reactions such as:

To explain the selectivity, we take a look at the reaction mechanism:

Considering that the insertion of the alkene into the $\ce{M-H}$ bond is the rate determining step (RDS), we can easily how sterics will affect the selectivity: More sterically hindered alkenes will lead to a more crowded transition state, thus a higher activation energy and a slower reaction rate. However, additionally there is an electronic effect which explains the selectivity towards alkenes with substituents on just one side of the double bond: Consider the partial charge distribution in the transition state, remembering that $\ce{H}$ migrates as a hydride:

As the stability increases from primary to tertiary carbocations and the other way around for carbanions, we see that the transition state is stabilized for substituents on just one side of the double bond rather than on both sides.

An interesting fun fact regarding the starting material of the above reaction: It can be synthesized from a molecule with out any double bonds (in DMSO, at elevated temperatures):

Dihydrogen Complexes

Hydrogen complexes can also appear as dihydrogen complexes, where the $\ce{H2}$ molecule is coordinated to the metal center as an $\ce{L}$-type ligand. As the ligand is not spherically symmetric anymore, there are multiple possible orientations of the $\ce{H2}$ molecule, which we examine in the example of Kubas complex:

Similarly to what we have seen for olefin complexes, the difference in stability between the two forms arises from the difference in $\pi$-backbonding. To estimate that we can setup the MO-diagram for the square pyramidal fragment of the complex for pure $\sigma$-donors and perturb it by considering the strong $\pi$-acceptor $\ce{CO}$ ligands:

As the energy of the $\sigma^{\ast}$-orbital is very high in energy, the more favorable interaction is with the energetically higher $d_{yz}$ orbital, which reasons that the structure on the right with $\ce{H2}$ in the $yz$-plane is more stable and thus adopted.

A related complex with $\ce{Ir}$ as the central metal also exists and shows an interesting effect of the hydrogen bond length being dependent on the other ligands:

This is observed since $\ce{Cl}$ is a $\pi$-donor ligand, whereas the hydride ligand $\ce{H}$ is a pure $\sigma$-donor. Consequently, there is more $\pi$-backdonation in the complex shown on the right, which leads to a longer $\ce{H-H}$ bond as the $\sigma^{\ast}$-orbital is populated.

Selective Hydrocyanation of Arenes

The hydrocyanation catalyst $\ce{[Ni(P^{\ast})(COD)]}$, where $\ce{P^{\ast}}$ is a bidentate, chiral phosphine ligand, exhibits an interesting temperature dependence in its $^{31}\ce{P}$ NMR spectrum in its active form, when a large excess of styrene is added:

The peaks can be assigned to the four different diastereomers of the complex (yellow peaks):

and the peaks of the inactive form (pink peaks). As the temperature is increased, the coordinated olefin ligand starts to rotate, which broadens the peaks and eventually they are so broad that they are not visible anymore.

A highlight of the hydrocyanation with styrene is that $\ce{CN}$ selectively adds to the substituted carbon atom at the double bond. This can be explained considering the mechanism of the reaction:

where $\eta^3$ coordination leads to additional stabilization and thus selectivity towards the shown insertion product over the other possible insertion product.